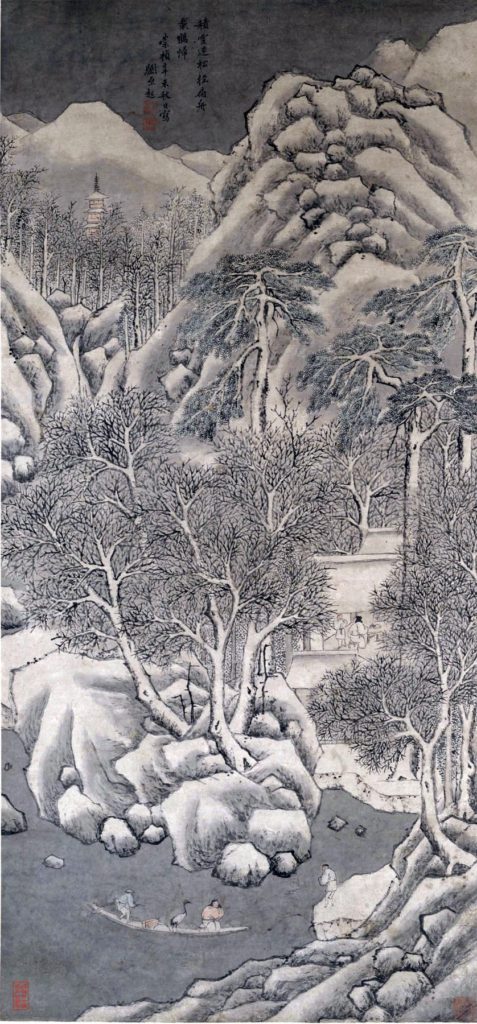

In a neighborhood free library, I found a crisp hardcover copy of Cold Mountain (1997) by Charles Frazier, but I gave it away to a man to read during his stay in the hospital. I borrowed a grimy copy from the library. I dipped in. There in the epigraph was Han-shan, the 9th century Chinese poet called the Master of Cold Mountain. I started Frazier’s Cold Mountain on page 292 and ended the chapter. Reading this way makes as much sense as wearing a robe of no-cloth or turtle’s fur boots (Han-shan #91). But there, deep in the novel, I discovered the lineage of the written word. Charles Frazier is a student of the Tao, an old and honorable pathless path.

Reading Frazier’s scene was also like listening to a long lost brother whose voice spoke to me directly; its Southern cadence and tone returned me to my novel’s hometown. Minutes later, I revised an early scene of my endless novel, The Compromise. My scene already had elements in common, especially how music reveals character in bitter-sweet tones. This has been a challenge, finding writers whose sensibilities and voice inform my writing. I often begin a new book with high hopes that are soon dashed. But I hope to stay with this cold mountain to learn what I can about the craft of fiction and the thematic lineage that Frazier and I share.

New Voice

“The dire keen of snake warning”

Cold Mountain, Charles Frazier

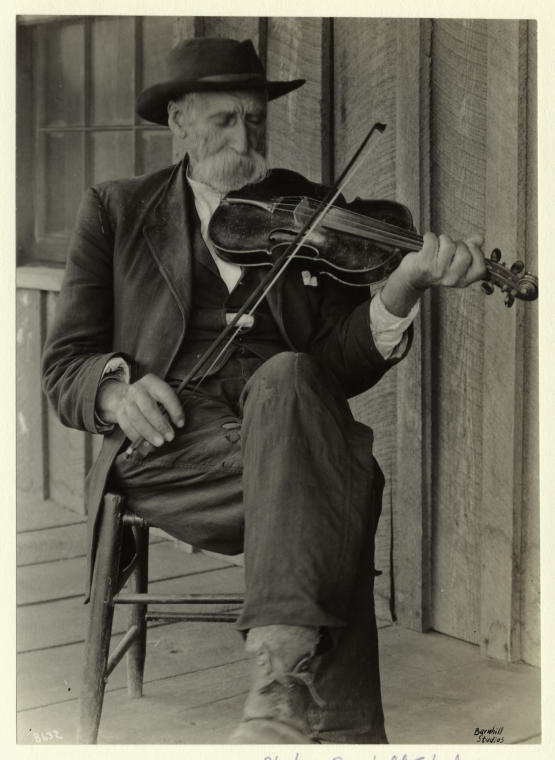

Frazier’s novel is set in North Carolina during the Civil War. It was made into a successful movie. A wounded confederate solider deserts from a military hospital to return to his hometown and his love. It’s a tragic story and cathartic. However, the protagonist of the novel is not featured in the vignette of my brief first reading. In this one transformative scene, the fiddler named Stobrod discovers his “new voice” when he plays his tunes for a dying girl. The scene begins when Stobrod cuts off the rattles of a living snake, a talisman to improve his fiddling, and it does. First, he speaks to the snake.

Live on if you care to, Stobrod had said, and he walked away shaking the rattles. He believed that from then on, every note he bowed would have a new voice. In it somewhere underneath would be the dire keen of snake warning (292).

The “dire keen of snake warning” is a serious word game. A shrill rattling sound contains the warning of grief, suggests Frazier, a grief that already exists inside of life; imminent, it has yet to arrive. This shrill and sharp warning is active underneath the melody, hidden in the vibration of sound. It hides in a literary voice. In the scene, it foreshadows what will come, and it is brilliant.

Listen to 20th century Appalachian speech and fiddle music here on Youtube.

The Duende

It must have been Frederick García Lorca, read in translation, who taught me about the duende. I do not see them as elves. They are more like the rattles cut from a snake. The duende can be felt as inspiration rising from the awareness of death, or as a poet of the world might offer, found in the silence hidden in the physical vibration of sound. Media vita in morte sumus. In the midst of life we are in death. The artist works here where embodied awareness, a secular transmigration, rises out of flat despair.

Here is the duende at work, peaking out of the serious game of words.

This meaning comes through in the story Stobrod relates to Ruby and Ada. While he was in military service, he was called to the bedside of a fifteen-year-old girl who was fatally burned in an kitchen accident. As she lay dying, she requests fiddle music. Stobrod plays his meager six dance tunes. But she requests something new, an original composition, which for this fiddler is nothing less than asking for a miracle. He delivers.

.... He set the fiddle to his neck and struck the bow to it and was himself surprised by the sounds that issued. The melody he spun out was slow and halting, and it found its mood mainly through drones and double stops. he could not have put a name to it, but the tune was in the frightening and awful Phrygian mode, and when the girl's mother heard it she burst into tears and ran from her chair out into the hall.

When he was done, the girl looked at Stobrod and said, Now that was fine.

--It wasn't neither, he said modestly.

--Was, the girl said. She turned her face away and her breathing grew wheezy and wet (294).

The simplicity and brevity of the dialogue is integral to the fullness of the prose, like a single instrument rising above the drone. He applies synecdoche, a literary device. Frazier uses the archetype of the emptying the cup, but it’s not filled with wine. The fiddler is offered a cup of milk to thank him for his tune. “By the time the cup was empty, the man had returned. She’s gone, he said…. You eased her way up there” (294).

Lighting the fire of inspiration, which is also the girl’s death by fire, returns as a motif very simply stated and emotionally displaced. “He had never before thought of trying to improve his playing, but now it seemed worthwhile to go at every tune as if all within earshot had been recently set afire” (294). Here is the duende at work, peaking out of the serious game of words. The author could not have planned this scene, says one who knows.

“He had never before thought of trying to improve his playing, but now it seemed worthwhile to go at every tune as if all within earshot had been recently set afire”

Cold Mountain, Charles Frazier

The Rule of Creation

Frazier takes the scene much further. The transformative effect of the initial event comes to the fiddler over years of work. He practices ritually and humbly at end of day. He learns from mentor musicians in taverns and across American cultures to build his repertoire and cultivate his self knowledge.

One thing he discovered with a great deal of astonishment was that music held more for him than just pleasure. There was meat to it. The groupings of sounds, their forms in the air as they rang out and faded, said something comforting to him about the rule of creation (295).

The fiddler continues to make discoveries within the single tune composed for “the girl.” Like the practice of Zen, the focus is on form– the groupings of sounds, their material forms in the air. The fiddler practicing the “rule of creation” in the mid-19th century reveals the sensibilities of a poet in any century, breathing with conviction.

“His playing was easy as a man drawing breath, yet with utter conviction in its centrality to life worth claiming.”

Cold Mountain, Charles Frazier

The tune was slow and modal, but demanding in its rhythm and of considerable range. More than that, its melody constantly presses on you the somber notion that is was a passing thing, here and gone, unfixable. Yearning was its main theme.... His playing was easy as a man drawing breath, yet with utter conviction in its centrality to life worth claiming (296).

Stobrod the fiddler survives to the end of the novel, not the young hero who opens the novel. Any reader should recognize how the fiddler stands for the author, philosopher and poet. Frazier knows the 9th century Zen-Taoist classic “Song of Cold Mountain” by Han-shan, the Master of Cold Mountain. The epigraph of the novel includes two lines by Han-shan. It is a dialogue as in a Koan and Cold Mountain speaks:

Men ask the way to Cold Mountain.

Cold Mountain: there’s no through trail.

Han-shan

Thematic Lineage

It looks like I took the path to Cold Mountain because I want to write more like National Book Award Winner, Charles Frazier. Okay. I like the way he makes his way as he goes. He brings the dark wilderness along with him, painful as it is. The thematic lineage seems Christian, then secular, then Taoist. His intellectual lineage comes through and I want it to come through me too.

But Frazier’s Cold Mountain is also about characters, and so is The Compromise. There is a psychological adventure when one sees how different realities are. One might think others are partial versions of oneself, or that another person’s life is offered as evidence of one’s own reality. That is how Frazier ends his scene. In Ada’s perception, Stobrod, “of all people, should offer himself up as proof positive that no matter what a waste one has made of one’s life, it is ever possible to find some path to redemption, however partial” (297). Ruby, on the other hand, is harsh. A looser is always a looser. A thief is a thief. Frazier is offering a theory of character but also a theory of social class.

Music

“Their tones braided like hair made of music and water.”

The Compromise

In an early chapter of The Compromise, Mariah wakes up from a long illness which befell her the night she arrived in a strange town to work in an unknown society of women. Others’ realities come crashing in on her sleep-opened senses. She is found lacking, unattractive, and unpolished especially when compared to her sister, Eliza. Death is social death against which to battle with endurance. But the allure of music is stronger than shame, however briefly. Mariah discovers music encased in privilege and must try to find the through trail.

Hester combed my hair pulling my head back. “You learn to wear a bun like the others, and make a small piece of lace so you look civilized.” She scowled and said. “You played dead and didn’t learn anything these three days while your sister--”

“Music,” I said with dryness in my throat.

“You hear that? Your sister is already in the parlor practicing for a recital. She’s everyone’s favorite, that Eliza. She’s got a voice, that one, singing Mozart by ear, they say. And she’s polishing up. Not like you. They think she’s a babydoll with that pink skin. You’re still grey under the eyes, or is that your color? But you’re clean, so you may go into the parlor to see the finery. Then, if you can stand up, come right back to help me in the kitchen, you hear?” Hester replaced the sheets on the bed, collected laundry, and left like a tornado picking up speed.

I had vertigo. When I moved the air felt thick, but I had to find the music coming from another part of the house. I walked carefully down a hall that was about the same size as our cabin in Stoneville. The music came from a room where three girls clustered around a big music-making device almost hidden by their full skirts. One was Eliza. She wore a white pinafore pulled over her pink-striped dress. She was matching the tones and her voice made the girls smile and nod. Another girl sang in a delicate voice and Eliza, with her head for music, picked up the tune and harmonized. Their tones braided like hair made of music and water.

“In my house there is a cave, and in my cave there is nothing at all–“

HAN-SHAN

Underground Rivers

Harmonies sound to Mariah like something she can feel with her hands, “like braided hair made of music and water.” Instead of cutting the “dire warning” rattles off the snake, it is the instrument itself which vibrates in harmonics like water splashing into an underground cave. The image seems distinctly more feminine. The springs and caverns of Missouri were established as a motif in the first chapter. The materials and the geometry of the space determine what can be created within it. Dependent origination takes place inside and among the physical forms. It does not guide from outside of them. It offers a theory of creation through interaction.

There was a river underground too. The girl’s fingers made it flow but something else made it echo and swirl. The tones came from a large wooden box up on legs with the finest wood carving I’d ever seen. I stepped in closer behind them. A girl pressed her fingers on black and white blocks, hand crossing over hand. The cabinet gave vibration to the air and to the floor and walls. The girl’s fingers lifted off and the sound circled the room. Then she said with petulance, “I want to play something else. This old piano is simply insufficient for arpeggios. Where are the études?”

Mariah steps in closer to contemplate the mysterious new harmonies and overtones, but she is also stepping closer to social disgrace. By the end of the scene, Mariah will have been identified as uncivilized and ignorant. Her sister will have distanced herself through her own need to be accepted. It will take years for Mariah to outgrow this shame.

The girl at the piano said, “There’s the new maid creeping around. Hey, new girl, what’s your name?”

“Mariah,” I said meekly. Eliza lowered her eyes.

“Fetch us some tea with bergamot if you have any. Hot tea, mind you, and be quick about it!”

The other girl called out, “Sugar and cream. Biscuits and butter.” To her friends she said, “Look at her. She doesn’t know what we’re talking about.” Eliza frowned and looked away.

I ask my protagonist to endure as a human soul.

The paths are different to this cold mountain. Charles Frazier more frequently calls on the transformative power of death. In contrast, I ask my protagonist to endure as a human soul.

I gathered myself out of the far reaches of the room where the music still lingered. “Yes, Miss,” I said with a stiff curtsey. It felt strange, like beauty and wonder had to be thrown out with the fish heads.

She must learn to bind a family amidst classism, racism, sexism, many social and practical hardships, and insipid cruelties. On this path, she is belittled and misunderstood until she is protected and strengthened by love, the kind that falls and with courage seeps up again.