Let each of us be invisibly added to the other’s powers of sentiment and reasoning.

The Compromise, “The Pulitzer Library 1841”

Formal learning is often both a gain and a loss. Hopefully, when readers come to the end of the first chapter, they will anticipate the risks as Mariah learns to “tame her wild heart.” She is leaving a way of life that many in contemporary society now want to regain. The rough passage out of childhood is a familiar coming of age theme. Her new situation will test her self-reliance and her loyalty to her mother. Indigenous and woman’s knowledge could free her or impede her. The thesis I am testing in writing this novel is that all knowledge frees us. Ways of knowing enrich each other. Learning in every domain and every tradition gives us tools when we attempt to understand our world.

Being wild usually meant thorns and bitterness. But I made friends with the wild plants and served them water in the dry heat. They weren’t bad. They gave me food, medicine, warmth, and shelter for my kindness. If taming the heart took years, I could put it off for another day.

The Compromise, “Stoneville 1839”

One of the themes of The Compromise is the importance of learning to read. My characters learn through music, scripture, conversations, ancient manuscripts, illustrations, narratives, and letters. Important action takes place in the fictional Gamble Library where art and manuscripts were donated for the education of young women in Missouri.

Teaching dark-skinned people in Missouri to read was illegal until after the Civil War. Some worked in secret to educate their family, neighbors, and enslaved workers. My character Hester Brown was more literate than her new coworker, Mariah Roche. As the Black Code tightened, teaching meant increasing personal risk.

I asked one day, “Hester, would it be wrong for you to teach me to read and write?” “I don’t know, Miss Mariah. I don’t know what the Codes say about colored people like me teaching not-very-colored people like you. Just sit in the library and copy those words until you know them.”

The Compromise “The Gamble Library 1841”

The Library

A great library is donated by the fictional Mrs. Gamble to the Columbian Female Academy. Both Mariah and Otis make use of the library, which was a rare experience in the period. To me, it is exicitng to consider. However, it is not of of particular interest to my beta readers– to read about people learning to read. Making knowledge available to all classes of people has long seemed essential to American life. The Compromise celebrates the library and the vision of educators to protect and shape constructivist learning. A library lets my character wander and explore knowledge before she learns to read.

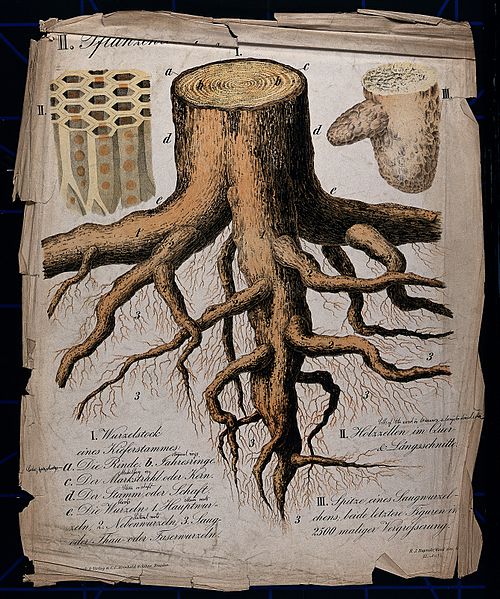

In 1840, a library could have had evidence of block printing, movable type, printing presses, etching, mezzotint, aquatint, lithography, and chromolithograph. Printing – Wikipedia Mariah begins by looking at picture books and meditating on time, representation, and beauty. She sees how books expand knowledge from individuals’ own time and place. She wonders if this solves the “problem of mortality.”

My favorite books did not require you to read a word. They helped you build things: a device for measuring angles, the tools of masons, a dial for telling time, a design for an arched doorway, and more watermills than we had in Stoneville. Page after page, the antlers of deer, the patterns on spiders, a pine cone, the formula of a wing, the bones of a hand, and the cross-section of a bone; books laid them out with reverence to show their holiness like I'd never seen before.

The Compromise “The Gamble Library 1841”

Considering a library, there were more voices in history than a person could hear in a lifetime, even as a chorus of continuous song. To hear just a few notes, I needed to learn to read.

Mariah had a difficult start learning to read. She had to push back on those who detracted from her curiosity and self-esteem as a learner. Her father thought reading was unnatural for women and tried to keep her from “getting ideas.” Mrs. Starr impresses on her the library rules which communicates her unworthiness.

I hoped Mrs. Starr would not show me the book darkened by mold that I had tried to clean, but she did.

“Even I must not open this book, Mariah. But you can see from the outside. It has tiny holes from bookworms long since decayed. Only special antiquarians know what this book means. We are not antiquarians, Mariah.”

“No, Ma’am. You are right.” But this one with the worm holes I understood. Worms had the final say, books or no books.

Learning to Read

She was a teacher and bolt of lightning.

Her first teacher, Miss Claire applied a pedagogy of humiliation. This came with too much information which was inaccessible. Mariah’s education begins in earnest when a true teacher comes, a young woman named Margaret Jane Mott, the fictional niece of Lucretia Mott, a famous reformer.

“She wants us to work together for equal rights, for women to own property, go to college, and vote.”

She said, “You will learn to read when you want to know what it says. You can cultivate your mind like a garden. This next one is written by an American woman living in Boston, Miss Margaret Fuller. Woman in the Nineteenth Century is a manuscript soon to be published in The Dial. She wants us to work together for equal rights, for women to own property, go to college, and vote.”

“Miss Fuller writes, ‘If you have knowledge, let others light their candles by it.’”

“I know how to light candles, but I don't know how to make sense of the words.”

She looked into my face and touched my cheek. “Don't give up,” she said. “The view from the summit is worth the effort.”

“Then you pull the ideas from the page like clusters of grapes from the vine. You will find they give more flavor at every turn.”

The Compromise “The Gamble Library 1841”

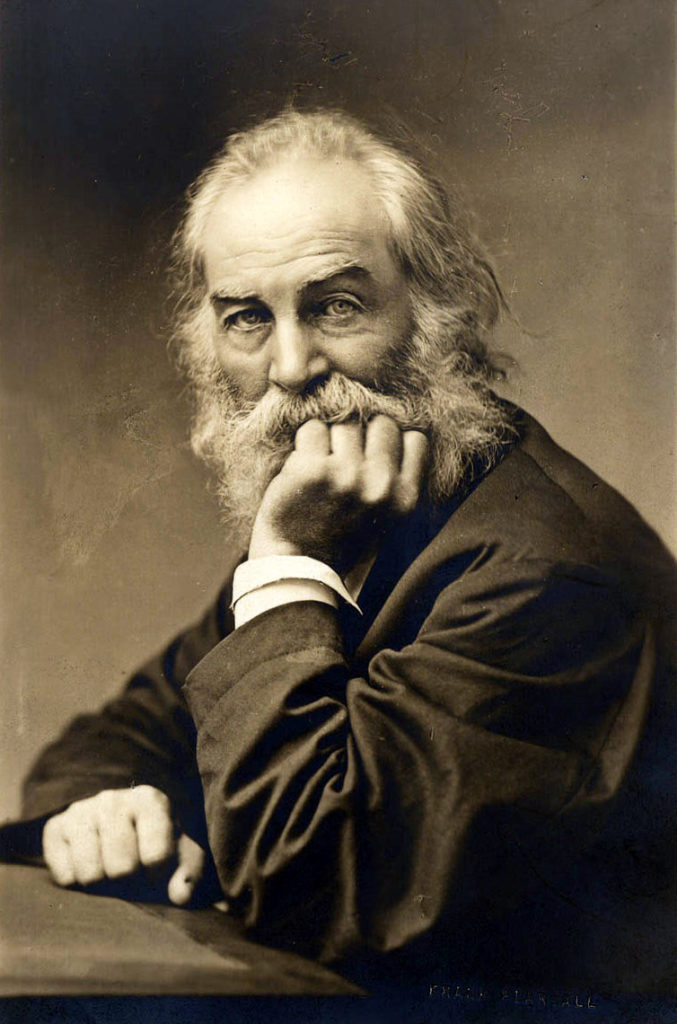

“Resist much, obey little.“

Margaret slipped some folded papers from between other books. Placing her finger over her lips she whispered, “The literary magazine, ‘Aurora’ has printed the poetry of Mr. Walt Whitman. He writes, ‘Resist much, obey little.’ And ‘your very flesh shall be a great poem.’” Margaret blushed. I noted the location of the manuscript on the shelf. This is what I wanted to read first.

The Compromise “The Gamble Library 1841”

Writing

Margaret says, “Letters are the library of the people.” She reads her aunt’s letters aloud to Mariah. Based on the writings of Lucretia Mott, they are letters of encouragement and introductions to the work of the anti-slavery society. Together they read letters between John and Abigail Adams. Letters, as much as newspapers, carried news that changed their lives and held them together.

Mariah also struggles to write. Her half-brother Otis is a gifted writer though not a patient teacher. It is not for many years, as disclosed in the novel’s epilogue, that Mariah trusts herself to write her story. Then it is through the prompting of her book-loving daughter, my great-great aunt Margaret. I smile to think of the many ways my mother encouraged me and I encouraged her. Her mother, whom I never met, had formal education from the University of California and the University of Washington. Evidence suggests that her father, Nick Hoffman, was a humorist. Delight in story-telling and love of ideas, including the classical notions of truth and beauty, must have come down the generations.

Learning from Nature

Written words are mere traces of the human spirit, but as such they are invaluable.

Mariah’s time with her teacher Margaret comes to an end. Reading Emerson’s essay “Nature” (1836) compels Margaret to experience the garden where Mariah applies her knowledge. For Mariah, this could be a new perspective on her indigenous knowledge. The sources of knowledge and the friends that leave us melt into the heart. Written words are mere traces of the human spirit, but as such they are invaluable.

One afternoon in the early summer, Margaret and I were in the garden on our knees planting potatoes, and she said, “We should remember this day.”

“Like John and Abigail Adams in the garden.”

She smiled that little smile. “Right. Let each of us be invisibly added to the other’s powers of sentiment and reasoning. It could honor us both forever after.”

I nodded and did not suspect those were parting words.

... I wrote down some of what she said on slips of paper that I kept in my apron pocket. “Once educated, we can keep our minds free while our bodies bend and break with trials.” I needed those words because I was cleaning and putting on meals for people who never really saw me as more than a cleaning rag or serving spoon.

Let each of us be invisibly added to the other’s powers of sentiment and reasoning.

The Compromise, “The Pulitzer Library 1841”

The University

Higher education was not yet open to women or people of color. Oberlin College is a great exception. The University of Missouri was founded in the year Mariah moves to Columbia, 1839. The siblings grapple with the fact that people like them build the structures, but do not use them except to clean them. Otis and Mariah are touched by academic ambition, but for Otis the dream leads to his arrest. Mariah becomes literate, but she must wait for her daughter and granddaughter to enter the university. Such restrictions could also lead to great passion for learning as it did in my family.

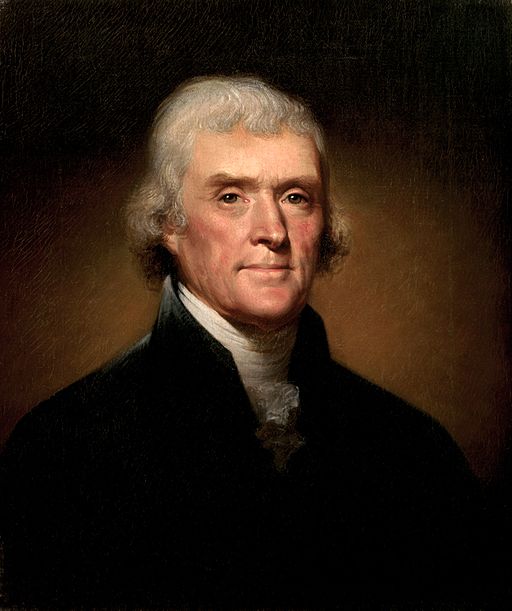

‘Truth advances and error recedes, step by step only.’

Thomas Jefferson

Otis led us south towards a place where buildings were being constructed that he said would stand forever.

“Stand forever,” mimed Eliza.

“This is the place! See the six limestone columns of Academic Hall? The University of Missouri is the first of its kind to step over the Mississippi. The ‘Academical Village’ is going to be here. It’s coming alive in the mighty and far-reaching hands of my friend Thomas Jefferson.” But we could see that the buildings were only marks on the ground except for the one before us that was still being built.

Otis told us to stay where we were. He ran up the steps to those six white columns and stretched out his hands to touch each one. He yelled back smiling, “Our liberties are limited only by our knowledge and by the equal rights of others! This is a family of ideals that will stand united forever!”

I knew then what Otis wanted more than anything in this world. His hands on the columns reminded me of Mother touching Stone Creek and of our pa holding the Bible that he knew by heart.

One day Jefferson’s words will not be lies.

“No, you and I are not welcome here now except to dirty our hands and dream.” He pointed back to the university and said, “Today the shapes of buildings are drawn with string and their designs are words on paper. One day Jefferson’s words will not be lies. My friend Jefferson said, ‘Truth advances and error recedes, step by step only.’”

American Education

My ancestors in the 19th and 20th centuries gave their lives to the future of American education. Simply put, my mother and grandmother were teachers. My great-grandmother, Mary Otis Fowler made personal sacrifices for her daughter Emma to attend the University of California, Berkeley and then beyond her time, for her granddaughter, my mother, Mary Helen. Here in Berkeley, I knowingly walk the same paths and enter the same buildings frequented by three generations of my maternal ancestors in the 20th century.

Those places remind me that history is made, not of blocks of time, but of overlaping arches where values are transmited multiple generations at a time. (My father, A. Ray Tolman, and his father, Justin Tolman, were also teachers and writers, as were many of their descendants. For about fifty years, a relation had our name on a campus building, Tolman Hall.) Directly or indirectly, they were building schools, libraries, and theories that became our bridges. My fictional character, Mariah Roche begins the story of independence and service in a Missouri library, but Mariah Roche is also my great-great-grandmother who must have been intelligent, kind, and brave. This book is my ode to all of them.