This cold morning, I am grateful to the midwife who worked in Rigby, Idaho in the winter of 1916. My father, A. Ray Tolman was born into a Mormon enclave in a house with no electricity. My grandmother told stories of how the warm water beside her birthing bed steamed and then froze in the sub-zero temperature. Their stories were framed by children, seasons, and weather conditions. I do the same as I write The Compromise: An American Novel.

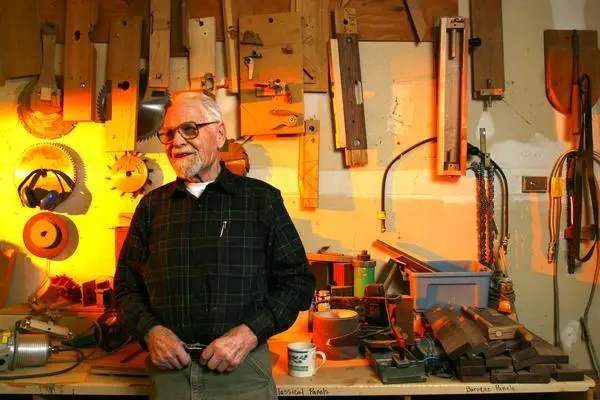

As a young man my father helped string electrical wires to homes in rural areas. He and his coworkers did not believe that electricity brought the sum-total of reality. It replaced wood, tallow, and oil. His foundational work was not in relation to an invisible supply chain. My father learned to run a saw mill, work with hand tools, frame and wire buildings, fix machines, pour cement, recycle building materials, make cabinets and furniture, and hunt game. He helped his mother and sisters preserve the products of their gardens and orchards. His mother taught me to embroider and he taught me to weave on a small loom of his making. Though I never stepped inside my grandparents’ church, Grandma Alice taught me prayers and I said them in her honor. Her voice and the light touch of her hand on mine taught me about her faith. There is knowledge I associate with them, at once practical and strange.

Labor was divided. This created different cultures for men and women, but the basic theme would have been the same. Work for members of my grandparents’ generation was in their hands, shared with the hands of God. Life became a study in humility and fragility in relation to divinity, not the Internet. Self-sovereignty must have informed my father. He computed with a slide rule and sketched his designs and observations on paper napkins. He left the Mormon church and embraced secular humanism along with elements of socialism and Marxism, but when and how, I can only speculate. He became an instructor of Sociology and Industrial Arts at Fullerton College in the 1960s. He served on the faculty senate and his colleagues became his friends. How my father held and adapted his beliefs as he lived into the 21st century delights me with curiosity and a dose of envy.

Like all children, I was unaware how he influenced me. That influence is discernible as I work and interpret the world, however. Along with my mother, he taught me that we are here to make things, to teach and write and so build a better world, not a perfect world or a transcendent other world, but a kinder, more aware, and equitable society. These values were handed down through education influenced by the European Enlightenment and filtered through new American religions. My grandparents’ religion was formed during the Second Great Awakening, a protestant religious revival in the US, 1795-1835.

For my parents, the goodness of humanism, a liberal arts education, and society’s progressive improvement were unquestioned. Their social membership was strengthened post-war by the GI Bill and careers as educators. However, it was through their generations, begun in the 19th century and spanning the 20th, that native people were scattered and silenced and Jim Crow and redlining divided us. The systems of oppression and the cruelties of othering were either actively hidden to benefit themselves or struggled against with the only tools they had. For them, the pen was mightier.

There is much about the power to read in The Compromise. Mariah uses aphorisms written by her tutor to give her strength. A teacher of basic skills for much of my career, I write Mariah who copes with exclusion and social distance. I witnessed my students’ kindness to one another and their firm grasp of the power of education.

I wrote down some of what Margaret said on slips of paper that I kept in my apron pocket. My favorite said, “Once educated, we can keep our minds free while our bodies bend and break with trials.” I needed those words because I was cleaning and putting on meals for people who never really saw me as more than a cleaning rag or serving spoon.

The Compromise, “In The Garden”

The 19th and 20th centuries were also the centuries of devastation to the environment as automation took work out of their hands. Cotton and wool were sent to factories to be woven and industrial sawmills changed forests forever. Loss of habitat and the healthy reciprocities of our work were the consequences. However, we can continue find ways to be reciprocally engaged with natural rhythms.

“That ethic of reciprocity was cleared away along with the forests, the beauty of justice traded away for more stuff.”

Robin Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, 2013

A Midwife’s Tale

Martha Ballard's diary rests safe in a vault at the Maine State Library, a monument to a remarkable life and testimony to the fragile web that connects one generation to another" (Ulrich, 352).

A recent discovery, another Pulitzer Prize winner, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary 1785-1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich gives us insight into rural American society through the daily experience of a midwife and healer. Midwife Ballard delivered an average of 40 babies a year. She worked among women in her community, only a few of whom could read and who wrote almost no chronicles of their lives. Through analysis, Ulrich discovers the midwife’s narrative and speculates on the norms and habits of her society. Those discoveries are based on her own contemporary norms of scholarship and her beliefs compassionately applied.

This work of American History and Women’s Studies became the subject of a documentary for American Experience. “A Midwife’s Tale chronicles the interwoven stories of two remarkable women: an eighteenth-century midwife and healer and the twentieth-century historian who brought her words to light.”

I also read Laurel Ulrich, for she is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Later-day Saints, the church shared with my progenitors on my father’s side. Though I never stepped inside their churches, their Mormon cultural values must influence my choices as I write. Like Ulrich, I look for ways fictional lives are complicated yet liberating.

“In January 2017, Ulrich’s book A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, was released. This text explores Mormon women living in Utah during the 19th century who had entered into plural marriages. Ulrich argues that this system was both complicated and empowering for the women in these relationships.”

Wikipedia

The historical Martha Ballard died only about thirty years before the opening of The Compromise. I read it for enriching new ideas and for confirmation of my historical fiction. Ulrich asks some of the same questions about the experiences of women in history. Like this feminist historian, I see their lives framed by the patterns of nature and shaped by our biology in complicated rhythm with society and technology. As a novelist, I seek to represent the truth of human experience in linked units called scenes, made into literature with imagery and voice. These scenes reveal as much about me and my society as “the truth” of history. Human experience is always, always more complex and profound than any artistic rendering.

Women’s Work

Who is not amazed by the complexity of men and women’s work, its division, requirements, and possibilities as industries and systems change? Martha Ballard and her daughters were engaged in textile production, carding, spinning, and weaving wool, as well as cooking and cleaning, maintaining records of quantities produced and sold, hours spent on tasks, payments and debts, medical care, manufacture of medicines, childcare, and eldercare. Ulrich has gathered these threads to weave the story and find the pattern where other historians saw trivia.

"Yet it is in the very dailiness, its exhaustive, repetitive dailiness, that the real power of Martha Ballard's book lies. To extract the river crossings without noticing the cold days spent 'footing' stockings, to abstract the births without recording the long autumns spent winding quills, pickling meat, and sorting cabbages, is to destroy the sinews of this earnest, steady, gentle, and courageous record"(Ulrich, 9).

Ulrich may be teaching us about the steady and mindful productivity of pioneer women, indeed, most women, including those who were enslaved. Here are reflections of loyalty, perseverance, and self-reliance that help us thrive, especially outside of official economies. Though I do not identify myself as a Mormon, I share these values and have given them to my protagonist, Mariah. They enable her to learn through adversity and mark her growth as a woman. My fiction also has a theory of social history. I look for interesting tensions when my characters participate in the construction of gender, class, and race in the distribution of work. A fictional rendering of oppression can include these stories.

Eliza climbed to the attic bedroom and made a promise to herself. I will not empty any more chamber pots, not even my own. She pushed hers under the bed with the side of her boot and pulled the bedspread down to conceal it.... It was the natural order, everyone agreed. Pretty things had to be kept special. Eliza Roche was a white girl and special among all the others. At this new place, she would become a lady, not a maid. Looking nice was the most important thing. That meant how she appeared at all times.... Her sister would do it for her, empty chamber pots and launder the rags. Her sister had always done hateful, dirty work like killing animals and cleaning up when people were sick. Mariah had that darker color to her skin and straight black hair that marked her as a primitive.

The Compromise, “Eliza Upstairs”

I have written this scene to show how Eliza invests in the signs of race to confirm her decision to pass her workload to her sister. It is part of a strategy to identify with a social class based on her appearance, and so raise her social status among her new peers. She decides that it is a natural division of labor based on physical racial characteristics, the very characteristics that are rewarded and reinforced by her society. I expect the reader to see the betrayal of her sister. For Eliza this leads to fragility of her ego, which could also be interpreted in Freudian terms.

“How does integrity face oppression, how does honesty face deception, how does decency face insult, how does courage meet brute force?”

Cornel West, 2021

The discourse on race is not my expertise, and I tend to see that issues of power come before issues of race. Power is relative and alterable through human agency. Race seen in these terms is a construction of power relations. These issues in the Compromise are explored, but not only through descriptions of large enslaving interests of the 19th century, though that period has left inequity in our systems. Because much of the oppression of slavery took place in the family, historical fiction should include stories of domestic entanglement, and these are largely stories of women learning to free themselves.

The protagonist’s internal struggle makes the narrative arc.

Work of Interaction

In a braided narrative, I can show the same event from the other sister’s point of view. Mariah sees her lowered station in the context of relationship and work. The protagonist’s internal struggle makes the narrative arc. I hope to show how race and class were integrated into the social fabric, constructed, and not the mass moral failings of a particular race or time in history. If I can circle back to the choices we make, I show how individuals can also change them.

I kept the orchard, the garden, the hen house, and did general cleaning and healing. Eliza and I heard our nickels ping in the money box. We kept our eyes open, but Eliza saw the girls upstairs, and they welcomed her, not me, with gifts of confidence and charity. She did their laundry and mending like a poor relation, and because she looked so pretty, they made her work light and even brought me their chamber pots to save Eliza the trouble.

The Compromise, “The Liberator“

While work separated the sisters Mariah and Eliza and their class aspirations, it brought Mariah into a daily rhythm with Hester, an enslaved woman, who is more emotionally mature. Together Hester and Mariah build a microcosm of shared work. I record the trivia and monotony yet spice it with rhythmical parallels and playfulness. While this lends voice to my fiction, it also says that the women of the past were much like women today, skilled at finding silver linings and making lemonade.

I thought I knew Hester pretty well by this time.... I cooked and she cleaned. She cooked and I cleaned. We took turns bringing down the chamber pots and cleaning the outhouse. She took care of maladies of old age, and I took care of injuries. I fussed with things that didn’t work, and she found fault. I lugged the water, and she boiled it. I opened windows and she closed them. She lit lamps at sunset, and I snuffed them out. From market, she carried the sugar and I carried the flour, and we each complained that we had the heavier load. She called me “Miss Mariah Milk Thistle,” and I called her “Sassy-fras Pester-Hester.” Sometimes "Hester-Pester,” but only on good days. On bad days, she called me “Miss Prickly” and she got “Meat Cleaver.”

Adaptation to material conditions is a virtue, the story says, and collective change is methodical and slow. If we survive our times, we are in it for the long haul, one generation after another. Mariah is developing the knowledge to make social change for her generation. If these tensions and playful interactions existed for Martha Ballard and her daughters, they were scrubbed from the diary. Why? They were probably deemed insignificant or self-indulgent in a Puritan society. Possibly social and emotional awareness required more time and leisure than they had. Without literacy and leisure time, they might not have been exposed to enough enriching and validating expressions.

But are we really that different when it comes to the material, interpersonal, or cultural work of women? Are we recognized for the work we do to hold our families and communities together? The sociolinguistic research of Pamela Fishman opened my eyes. I began to read the data in front of me more critically.

“Women do more conversational work than men; this is the interactional manifestation of power relations.”

Pamela Fishman, Interaction: The Work Women Do, 1978

Interaction is like a shuttle working a loom and a text, a patterned textile.

Women’s Invisibility

"Day by day women negotiated the fragile threads of ordinary need that bound families together.... If women had a collective consciousness, it was surely developed in such work" (Ulrich 100).

Ulrich’s scholarship clarifies the historical context of one of the most important themes in the Compromise, how women endure and reinforce their own invisibility, which has a long history in the making. Ulrich is able to contrast the record of women’s work with the official records of men’s work and the institutions that developed around them.

"Town offices reflected the major commercial products of the commodities men shipped down the river into the streams of international trade. They also reflected male ownership of the land, buildings, and cattle, some officers being responsible for the maintenance of public buildings and roads, others for surveying the fences..."(Ulrich 100).

"Women's invisibility in town records reflected the patriarchal organization of society as well as the perishable and invisible nature of their work (Ulrich 100).

In these ways, society managed the boundaries between public and private. The body, its health and illnesses, reproduction, clothing, food and childbirth were more fragile, requiring steady work of binding parts together. The midwife’s record, which quantified and professionalized women’s work may have been transgressive in her time. What is recorded as significant or hidden with reticence is precious evidence of social history as well as character.

All women may face this history of pressure against their voices. Writing could make our ideas endure when they are otherwise deemed forgettable, perishable, and ordinary. My writing about the domestic work of women has been personally revealing and liberating.

What is recorded as significant or hidden with reticence is precious evidence of social history as well as character.

My artistic response is probably conventional, to cultivate the novel’s charm, wit, and beauty. I hide its special intelligence, waiting perhaps in vain for my work to be discovered. Yet my creativity flows when I speak through this hidden and protected quality of myself.

The Binding of Fragile Threads

Let’s consider artistic choices made near the end of the novel. Near death, Eliza enters an altered state, which gives her both clear and numinous perception. Visual and auditory imagery might show that she is free of a bounded self.

Still higher, Eliza could see where she was for the first time. She looked down the long roads, cutting and drumming the soil; the river, its deep and surging drone under glistening bells; the city, its sharp-edged clatter and ships creaking at the wharf; the hills, their dark green voices layering into the blue. She spread farther with every moment.

In the chapter called “Eliza on the Road,” I use the image of threads that bind, much like the “fragile threads of ordinary need that bound families together” in Ulrich’s metaphor. The reader should know that Mariah, unattractive and plain to the point of invisibility, holds the unconscious young man in the saddle in front of her with the ropes she braided from prairie grass. In her sister’s altered state, Mariah, whose social identity is unrecognized, appears to radiate with light. Her threads, like sutras (meaning thread in Sanskrit), are the spiritual embrace of the world.

A horse and rider came to the crossroads and stopped. A man she had once known, so fragile and pale, was ticking in two-four time. Weak and only partly there, he was held together with threads and from behind by arms of light. It was her darling lover, Blu, the life force pulsing to free itself of him. Eliza told him to stay and live.

She studied those arms of light around him. What were they, so strong and silent when everything else made sound? They came out of nothing but held the sky to the earth and became a bridge she could step cross. This span was love and effort was unnecessary.

To me, this scene and another which follows told from Eliza’s point of view, form a significant resolution to the problem of their ideological rift running through the center of the novel. But I’m sure they will invite multiple interpretations. As one star sets, another rises.

“If women had a collective consciousness, it was surely developed in such work.”

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale