Writing, I’m always grappling with questions of style, structure, pace, history, and authenticity. My foremost challenge, however, is to build subjectivity for my narrator, a voice and a worldview. I must do it with a string of words, more than 100,000 of them, which enable a projection of the reader’s own humanity. To do this, I use my own habits of observation and reflection. I reach into myself to find the images and the voices. It is a sustained effort of reaching and gathering. They pass through emotions: patient yearning, tender hearted, and ironic. They come from what I know and what I never fully learned.

It is a sustained effort of reaching and gathering.

I am challenged to look at issues such as religion and race through the best contemporary lenses, yet to be creative I need to take risks. I face the problems all writers have in determining the relationship of the narrator to the dramatic action, close or distant. I reach for words and know full well that I cannot use the dialects of the past. I can use and sometimes approximate authentic language. As readers, we often compare a text to the “fabric of human experience” indicating that there are patterns woven in, which can be worn and interpreted. As a writer, I do the weaving. The richness of the pattern is determined by how I meet my challenges.

The richness of the pattern is determined by how I meet my challenges.

Describing Religion

I hope to present religious ideas respectfully, without promoting faith or cynicism.

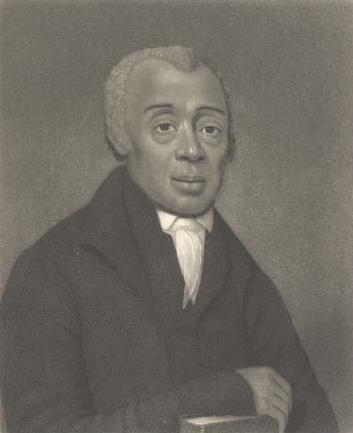

Describing religion in writing is a balancing act. Can I write fiction about people’s deeply held religious beliefs without sounding like I’m prostlyizing? My intellectual heritage on my mother’s side is associated with American Transcendentalism, an Englightenment philosophy that distinguished itself from sensualism. Could this family connection make me a didactic writer or a hypocritical one? Transcendalists believed that they were doing the work of God as they sought freedom and equality in American society. They worked for the abolition of slavery and better civil rights. They used education, prayer, writing, and mild, probably domestic forms of civil disobendience. My novel gives voice to these ideas. One of my personal quests is to trace my grandmother’s beliefs in the Christian Science teachings of Mary Baker Eddy back to the ideas of her mother and grandmother. In doing this, I may sound more religious than I intend. I hope to present religious ideas respectfully, without promoting faith or cynicism.

These Guidelines support [the] constitutionally sound approach for teaching about religion in public schools—encouraging student awareness of religions, but not acceptance of a particular religion; studying about religion, but not practicing religion; exposing students to a diversity of religious views, but not imposing any particular view; and educating students about all religions, but not promoting or denigrating religion.

[A cultural studies approach] helps students recognize that religion is a part of the fabric of human experience and that in order to understand it one must consider religious beliefs and practices as they shape and are shaped by all elements of culture.

Guidelines for Teaching About Religion in K-12 Public Schools in the United States

Learn more about how I treat religion in the context of birth and death in the post, Solemnity and Joy.

Representing Race

Representing race is another challenge. We can question the accuracy of an author’s sensibility and the authenticity of her voice. My current solution is to listen to people with kindly spoken and inclusive points of view on race. Best-selling author Francine Thomas Howard told me, “We are all on a moving path towards understanding race.” Of course, art is the mirror of that path and the printed book is a snapshot in time. Read a post about cultural appropriation here.

We are all on a moving path to understanding race.

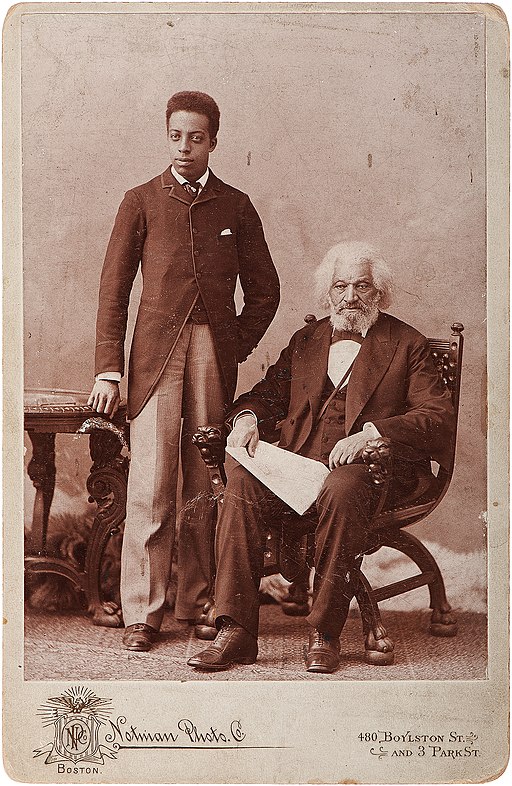

The character of Otis lets me explore what novelist David Wright Falade explores in his upcoming novel Nigh On a Brother (2022). Falade’s characters are related by blood: an enslaver father, an enslaved son, and a white cousin caught between them. The family endures the illogical pressures of slavery and is reshaped by the approaching Union Army. A recent article in the The New Yorker explains the complicated backstory:

What is equally important is that fiction allowed me to probe an under-explored aspect of their lives—racial mixing. So-called “miscegenation” has for much of our history been taboo, even as it was also very common, especially in the South. It remains taboo in many weird ways. Yet, from my view, it is what defines “Americanness.” Hybridity.

David Wright Falade, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020

Interpreting History

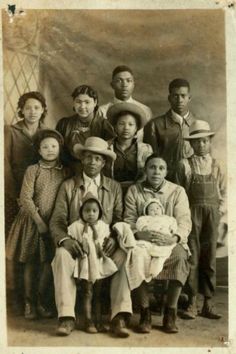

History has to be interpreted through the lense of the present. I knew far less history than I realized going into my research, so why write historical fiction? I do not prove that the past was barbaric and therefore emotionally entertaining. I don’t want to suggest that the past has better charms, more comfortable gender roles, or more understandable hierarchies. After all, they made huge mistakes, such as enslaving men and women, denying suffrage, taking lands and livlihoods, cutting down too many trees, and fouling the waterways Rather, I want us to see the lineage of history. The ancestors who lived in history are flawed and courageous in the same ways we are now.

To accomplish this, I need to represent the past with integrity, neither glorified nor denigrated.

Each new situation in which we find ourselves is a place for learning, be it a cabin, a convent, or congress. Literature can take us to those many places by calling on the past. To accomplish this, I need to represent the past with integrity, neither glorified nor denigrated.

I am researching the history as I write and real cultural gems inspire my story. In addition, our modern infrastructure began in the 19th century: transportation, public education, hygiene to name a few. The Compromise has scores of notes and references to interest a broad range of readers. My goal is to try for the psychological experience of history; it is not a setting only for facts or ridicule. I want the reader to be curious, to feel that interesting estrangement from her habits, for example, to recall how important clean water and fresh food are to daily life, how empowering it is to be economically self-sufficient, and how refreshing it is to keep one’s own counsel, and how essential it is to work for equal rights and social inclusion.

The moral dilemmas of the past were probably much the same as today. In a way, our personal lives, our social systems are the proof that the people of the past suceeded. How did they succeed? Was it through teamwork, effort, and compromise?

Our contemporary perspective heightens and clarifies these conflicts as they could have been lived.

Otis continued. “It’s called the Missouri Compromise, and we’ve been living under it since 1821. Maine entered the Union as a free state. Missouri joined as a slave state to preserve the balance of power in Congress.” He said this like he was proud to know it. “This compromise is delaying a fight, probably a war.”

“War?” asked Eliza. “That sounds bad.”

"Pa says its going to be easier to save a soul than save the Union."

The Compromise, Stoneville, 1839″

Much is written about the history of war, but The Compromise is not about the Civil War; this generation’s conflicts were often about the divisions that led to war. Our contemporary perspectives heighten and clarify these conflicts, and I try to write them as they could have been lived.

I also hope to show the optimism of the 1840s but qualified for the contemporary reader, who has learned to think critically. My narrator reflects on the events of the year in which she lives.

The United States was forming under our feet. The Democrats said it was growing without end and it seemed like we were too. John C. Fremont crossed the mountains into California and circled back to Missouri. The Millerites suffered their “Spring disappointment” in March and six months later, the “Great Disappointment.” The world did not end. That means, we said, we had to do the work ourselves. President Tyler opened the door of the White House to shake our hands and there was work to do. Texas signed on to join our growing union of states and then got lost getting here. Samuel Morse tapped out “In God we trust.” News could travel like the wind, at least between Washington and Baltimore. The rails were not here yet, but they were coming. Though the nation happened beyond the horizon most days, we were walking into a better world. That is as long as we didn’t look too hard at where we’d been or what was happening in the next town.

Writing Dialect

Diction and dialect, along with history, are always in question. Being authentic by using the dialect of the period, for example, by borrowing language from enslaved people’s narratives or Creole speech, could mean losing a non-linguist or even an inexperienced reader very quickly. I can also borrow language from the published works of the time, but those often represent the educated few whose standards we have adopted. To balance, I have taken language from published letters, newspapers, and song lyrics. I frequently use expressions handed down to me from family. My father was raised in Idaho and Utah and his speech patterns indicate pioneer roots. I edit for diction that is not too academic or heightened poetically, but still somewhat formal. Thus I often work with competing agendas and worry that fine editing could require years.

Even approaching authenticity makes my head swim, such as different strata of society, regions, migration patterns, genders, and ethnic backgrounds. Rather, I aim for variations of diction that are neither unbelievably contemporary nor inaccessible. I try more features of spoken language in dialogue and more features of written language in description.

I see dialects as a very challenging balancing act.

I have worked with knowledgable peer editors who help me work towards authenticity of Black English for some characters. I listen to people from the mid-west and listen to their idioms and intonation, but my analysis is far from scientific. My audio recordings are simply entertaining. I would like to include some Ozark speech and have called on friends of friends to advise me. I am very grateful for this help, but I still see dialects as a very challenging balancing act.

To improve some dialects in The Compromise, I can be informed by narratives set down a few decades after the 1840s: Salvery’s Echoes: Interviews with Former Missouri Slaves. However, there were no early recordings made of these narratives. They are contemporary interpretations of stories written after the Civil War and recorded for the Missouri State Museum. Following is an example of a narrative told by George Billinger of Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

“Aunt Polly en mammy allus know’d what to do when a body waz ailln’. Dey alus had a bag o’ herbs hangin’ under de porch.”

Audio Quotes from Former Missouri Slaves via Missouri Department of Natural Resources’ Missouri State Museum

First-Person Narration

Narration is another problem. Having a first-person narrator tell the story means that the point-of-view is never omniscient, always part of character. Then a turn of phrase or a cliche is never the author’s. Showing off as an author would undermine my narrator. Fine, but how much reflection does the narrator have on the events that she relates? Could she be speaking from a distance of years, such as by telling the story later in life? If she does not have critical distance, I lose literary qualities and risk dumbing down the narrator’s perceptions of her own life. My narrator is poor and disenfranchised but literate and living in conditions that enable knowledge of self. I work to keep her voice, not mine, in front of the reader. However, my learning, my deeper questions about my family and the human experience will be found in the narrator.

I work hard to simplify the voice by turning my phrases again and again.

One great trick of literature is to let the reader know what the narrator cannot apprehend, the unreliable narrator. A reader who can see past the narrator’s naïveté and self denial could give her the very things she and I would value most, the reader’s affection and concern. The social position of the author in the mind of the reader complicates that relationship. This is made apparent in the writing groups that critique the writing. I work hard to simplify my voice by turning my phrases again and again.

When true simplicity is gained

To bow and to bend, we will not be ashamed

To turn, turn, will be our delight

'Til by turning, turning, we come round right

Simple Gifts, Shaker song by Joseph Brackett, 1848

Welcoming Words

Language is my only tool. I cannot shake the reader’s hand, but I want to be welcoming and invite emotional bonds. Then by taking risks, the reader might explore intimacy with him- or herself. I ask the reader to trust the narrator, and let the narrator speak as a friend. This is why I try so hard to get the words right. In the American psyche, trust and simplicity are earned.