A library encases cultural bounty that may change the direction of our lives. Scenes of The Compromise which are set in the Gamble Library attempt to show that learning is constructive and generates consciousness. Ideals are discovered, tested, and remade. Learning here enables an understanding of relationships, social identities, political values, and spirituality. These affordances, the story aspires to say, come to each of us through generations of cultural knowledge and broad societal work to provide the conditions. Not all of us are educators, but not one of us is excluded from the responsibility of securing these for others. Several characters take form in these scenes: a wealthy benefactor, mentors, activists, teachers, and teachers-to-be. And the texts that come alive in the library include those written by Cicero, Pericles, Jefferson, Adams, Keats, Wordsworth, Austen, Emerson, Fuller, Childs, and Whitman.

"You have persisted," said Miss Claire, "but what have you learned?"

The first version of this essay was posted in August 2021. It discusses a precious, yet often unrecognized phase in development in which we lay our foundation of knowledge. How we learn creates patterns of growth throughout a lifetime. It includes textual and visual literacy, dialogue, independence, and trust. Few aspects of life could have as many consequences, and yet such learning could never be measured or systematically reproduced. What is deep and durable requires effort. Learners make mistakes, are susceptible to illusions, and even fail. Everyone who writes to learn knows this very well.

“It’s not the failure that’s desirable, it’s the dauntless effort despite the risks, the discovery of what works and what doesn’t that sometimes only failure can reveal.” – Peter C. Brown, Making it Stick: The Science of Sucessful Learning

Coming of age in a library does not compare to fighting dragons or saving the world, but here it is, a gift and a fiction. Six thousand words of the Compromise take place in the Gamble Library, 1841 to 1843. In historical fact, with a donation of $1,000, the University of Missouri library began in 1841 and had four thousand volumes by 1848. My Gamble Library is an improvement on history. The fictional library has books to the ceiling, paintings and prints, a globe, maps, architectural drawings, ancient manuscripts, the classics, new literary fiction, philosophical essays, unpublished work copied by hand, the New-York Daily Tribune, and contraband abolitionist newspapers. Almost exclusively, women were not allowed into university libraries, and public libraries came many years later after the Civil War. Even so, a benefactor could have donated her treasures to the education of all women.

Mrs. Gamble was lit by coral light coming through the window. She looked west and spoke to no one in particular. “Our dusk is already another’s dawn. Let my sunset be a morning star.’”

Turning, she addressed the room in a full musical voice. “Miss Ada, Mrs. Starr, I have made my decision. I will donate the Gamble Library to the Columbian Female Academy on the condition that these young women are educated!” She added and pointed at Eliza and me, “Including the girls from the hills.”

The Compromise, “Mrs. Gamble and Mrs. Wallace 1841”

Enormity of Knowledge

In the library, Mariah feels curiosity, wonder, intimidation, boredom, and envy. She learns to read, yes, but before that, she wrestles with the evidence of a civilization, its materials, chimera /ki-mi’ra/, languages, rules, and measurement of time. Comparing her own upbringing to the sophistication of an educated class is a major hurdle. One of the pains of learning is finding out what you don’t know. In the language of transformative learning, Mariah experiences a series of disorienting dilemmas. The school director tells her the rules, starting with “don’t touch the books.” Despite feeling ignorant and unworthy, my dear protagonist perseveres.

Pointing at me, she said, “You are never to touch them. Relics come from the saints, so they have special healing properties, not for common people to touch.”

“Yes, Ma’am.” I did not tell her that I had touched many books including the ones wrapped in silk down in the cedar boxes.

“Here is a medieval manuscript in Latin illustrated with gold. Scribes in Ireland painted these in the twelfth century.”

I asked, “Were scribes little people?”

“Like fairies?” she laughed. “No. Young men with good eyes, I reckon. Imagine their tiny paint brushes.”

I said, “Small as the stingers of bees.”

“Never let these pages see the light of day or the colors will fade and disappear.”

“Yes, Ma’am,” I muttered. I had already taken the pages into the garden to hold them in the morning light.

The details in these scenes come from my excursions to libraries and museums. I describe scraps of papyrus with hieroglyphs, darkened mold on books, holes of bookworms, and illuminated manuscripts. At age eighteen, around Mariah’s age, I strolled wide-eyed beside my mother through the British Museum, the National Gallery, and the Louvre. I looked up into the Sistine Chapel and smelled the dank air of catacomes. We were tourists. I was on the brink of womanhood and must have pocketed the memories. I had already taken a school trip to the Huntington Library and a youthful spin through the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress. That was beside my father who said they had his WPA sketches and watercolors down in the vaults. I imagined his artwork underground in the nation’s library. Even if they were in a box, ruined, or lost, I must have felt his pride and place in American history. My parents gave me these treasures and had no idea what they would mean beyond their time.

“Books almost fixed the problem of mortality.”

Maybe to me words looked like signs of caterpillars in the garden, but to a reader they could be music. Books had the marks, but readers made the song. In a library, there were voices all trying to speak, more than a person could hear in a lifetime. To hear a few of them, I needed to learn to read.

Why should a bunch of rules keep me out? The knowledge of centuries should belong to everyone even if the oldest books had to be hidden away so they wouldn't turn to dust. I chewed on these thoughts like a cud. People, being made of flesh, did not look good or live for very long, so they needed books to last longer. Books crossed centuries and oceans, and someday, maybe even the sky. They almost fixed the problem of mortality. But I still could not read.

“You’re making it harder than it is,” said Hester. “Sounds like those old books looked back at you the wrong way, like you’re inferior. Is that what you want?”

Conventions and Curiosity

“Even so, you must persist. Copy these lines one hundred times.”

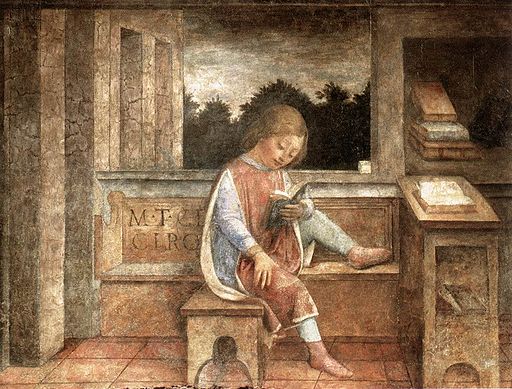

Mariah is waiting to learn to read. A Latin teacher, Miss Claire introduces her to Cicero, which at first seems like a poor pedagogical choice.

She placed a gold lorgnette on her nose. “Look. Cicero lived from 106 BC to 46 BC. Beheaded of course.”

“Be-headed?”

“Executed, decapitated, ‘off with his head.’”

I was impressed until I thought about it. “106 to 46? How’d he get-- de-headed before he was born?

“That’s an ignorant question. Ignorant: unintelligent, dull-witted, moronic. Even so, you must persist. Copy these sentences one hundred times.”

Resistance

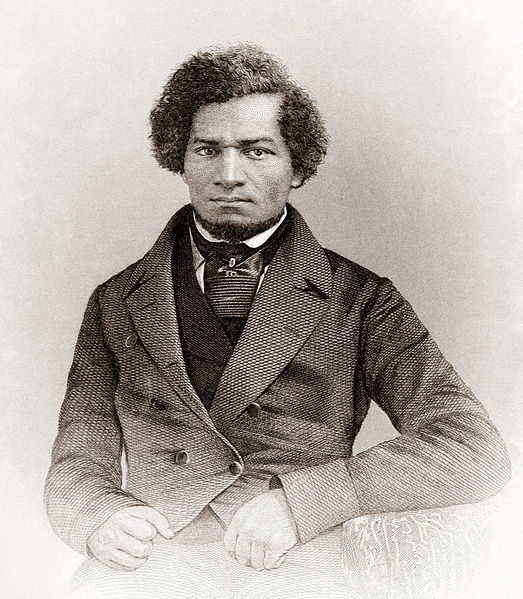

Mariah cries tears of boredom. Otis comes to admonish her for not having the proper attitude, but he also tells his story and gives her advice. He explains how he learned to read when it was prohibited.

Pa stopped me from reading, even beat me for it once, but I learned because I wanted to.”

“How? ‘Cause they say you can’t when you’re colored.”

“Shan’t, not can’t. It’s prohibited, not impossible. How? I stood on a stump and looked in the schoolhouse window. Then a white boy broke the rules. He taught me to read The Columbian Orator. Don’t let stupid rules hold you back, nor ignorant ideas neither....”

Otis said, “Those ancient Greeks, like Perecles, believed that they could make their own government because humans have the power to make themselves. You have power when you do it yourself. Pericles said, ‘The secret to happiness is freedom. And the secret to freedom is courage.’ Otis picked up his book and left, saying, “If this is what you want, don’t give up, no matter what they tell you.”

Every interaction in the library has consequences, including the advice from her brother that she must reasonably resist unreasonable rules, and set her own course. Many details of my character Otis are based on the life of Frederick Douglass, including how he learned to read and become a man of letters. The story of Mark Twain learning to read in a Missouri library is also here in spirit.

Clearly, Mariah has a streak of impiety that questions and resists authority. A later addition to the scenes in the library involves a racist image of the “natural order” that was popularly understood at the time. It represents a pyramid with a singular man above the “lower orders.”

I found a design that made me stop and wonder. It was a drawing at the top of the page of a light-skinned man with a pointy nose, his arms outstretched like a star, and kneeling to one side was a light-skinned woman holding a child and beside the child was a dark-skinned family of little people looking up at the man like he was the king. Under the people was a tiger and near the tiger was a lion family, and under them were hooved animals, horses, sheep, and antelope, and then the small animals like beaver and squirrel. There were birds and bees. Under them were the trees, grasses, and seeds. The lowest were the rocks, pebbles, and hills of sand with a trail of ants, tiny mushrooms, worms underground, and a coil of snake.

It was nice and orderly, so I wondered if it was true. Did the lower always giving their lives to the ones above, their bodies’ labor and blood? I turned over the book and tried to read the pictures upside down. Sure enough, the story changed when the ants, the worms, and the snake hung from the sky and fed on all orders of life below.

Turning a concept on its head is one of the most useful cognitive exercises I’ve ever known. It applies levity to gravity. It is a quick and easy way to “change the narrative,” at least in one’s private thoughts.

Discovery

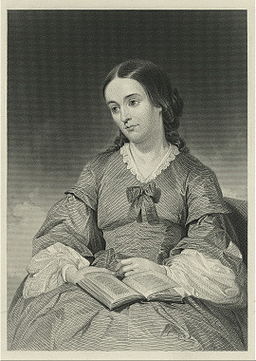

Eventually a teacher comes, Margaret Jane Mott, who stays beside her for a year that even I would envy. First, she hears about women writers, including Margaret Fuller, and there she discovers common cause and purpose.

I repeated, “Own property, go to college, and vote.” A jolt went through me. It moved a bolder and a river inside changed its course. That’s what I wanted. I wanted my own land. I wanted no end to what I could do. Every woman, rich or poor, able to read or not, had a common cause-- to have more say in how people lived together and that’s to vote and speak up, proud as an equal. If laws could change, it meant we could make our lives better, make laws fair for everyone, give Otis his rights and his freedoms and all the rest of us.

I held my notebook close. In there it said 100 times, “Not for ourselves alone are we born,” and that was old Cicero without his head talking to me from two-thousand years ago.

Margaret waited beside me with a smile. I looked at her in astonishment. She used the corner of her pinafore to dab my face. She was not a superior rich girl who cared nothing for working girls in the kitchen or the laundry. She was a teacher and bolt of lightning.

“When you read, you pull the ideas from the page like clusters of grapes from the vine. They give more flavor at every turn.”

Wrting this scene, I try to foreground a moment of learning, flatten the diction, and sharpen the metaphor. There are many transformative moments when knowledge cascades, time warps, and the path is revealed as if from a height. Her first great cascade of intellectual freedom compels her to posit the freedom of others. A youth matures in these moments. They come throughout adulthood in private contemplation of art, philosophy, or nature, and by noticing the fine suturing among them.

Pointless fear and self-doubt are dragons to slay and the freedom to learn is a land to protect. I believe that one teacher or one writer can change the course of many lives, and one life changed this way changes many more. I have been singing this song to very few, threading my story among the still-living memes. I am the first one to learn here.

“Not for ourselves alone are we born.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-46 BC)

Mimesis

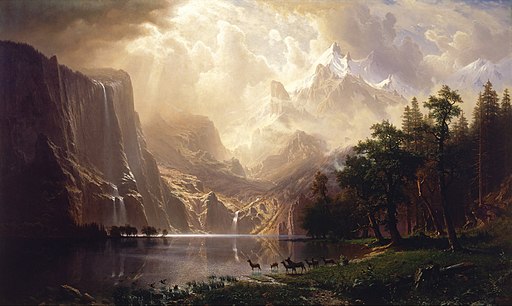

Two facing mirrors in the Gamble Library remind Mariah of the lake and sky and the latent divinity within. This is a Transcendentalist ethos, but even that is deftly questioned by my brave protagonist. Two frames with one person inside, are they both real?

In a narrow passageway, there were two mirrors facing each other. This was like looking at a lake full of the sky, and thinking “as above so below,” but never knowing for sure where or how it all began. Here in the library, the mirrors were only frames with a person inside. Looking at myself this way, maybe I was infinite too, and clearly I was only one person. Or that was a joke. So this was a library! Curious, I started opening books.

Sense of History

“They could not know if our democracy would rise and fall and rise again, and neither can we.”

After learning to decode with the McGuffy Readers, Mariah reads poetry and turns to history and government. Margaret takes a critical view of US history. Through reasoning abilities and by holding assumptions up to her chosen knowledge, Mariah critiques slavery and the philosophy of Manifest Destiny. She takes a step forward in the dialectic of her age. Mariah walks as an equal to her mentor. The teacher has lit the learner’s candle, and both lights are carried forward. Indeed, both are real.

"Empires rise and fall. Jefferson and Adams knew this. They chose to build a new colossus despite the lessons of history. They could not know if our democracy would rise and fall and rise again, and neither can we.”

“It takes courage,” I said.

”To live with the knowledge of history,” she finished my thought. We both smiled. I had picked up her habit of a quick half smile. Then we each took a lamp to retire for the night, she to her upstairs chamber and I to the little room off the kitchen. That night we watched the other drift away like a lantern on a lake. The phantoms of the ancient books seemed to move aside to let the living pass.

Political Activity

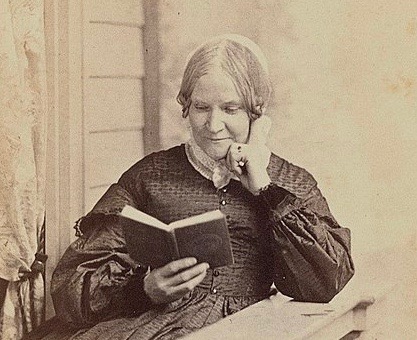

A secret antislavery meeting is held in the library. The guest speaker is historical figure, Lydia Maria Child. The meeting becomes contentious with shouting and shaking of fists. For Mariah it is a lesson in democratic process when a group is already polarized. The issue under discussion is whether or not to deny donations to schools and charitable institutions that enslaved workers. The guest speaker is rousing.

“To please the rich, prejudice withholds care at hospitals and bars admission at schools. If the children of the poor and despised are to be excluded to please the rich and the proud, let it not aggregate unto itself the name of a benevolent institution.”

There was general applause.

“Therefore,” she continued with fierce precision, “we must not give our gifts to any charitable institution which withholds its bounty, our bounty, from those who have the most to gain from it!”

There were shouts of approval followed by a tense silence.

Lydia Maria Child confronted racist institutions with these words as reported by Deborah Gold Hansen (1993) in Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Anti-slavery Society. Margaret and Mariah, each in her own way, defend the democratic process, but will they defend the Columbian Female Academy where enslaved labor is close to home? It means a parting of ways only seen by reflection.

Difficult Mastery

“It was more like hiking up a mountain through a cloud, which does not give way until it must to steady going, step by step.”

The Compromise “McGuffy Readers 1842”

Mariah learns to read with difficulty but reads well. Reading fosters stillness, which requires trust and an earned sense of belonging, the slow and mutual work of teaching and learning. In the world I have made for her, she even overcomes the dualistic earthly claims of pride and shame, self-doubt and betterment.

I could sit there moving only my eyes over books of poetry and the singers sang to me a private chorus. For me reading was not like pulling grapes from the vine. It was more like hiking up a mountain through a cloud, which does not give way until it must to steady going, step by step. Above the line of clouds, the sky widens to moonlight and stars and the rim of earth, this shaking, monstrous, beautiful place. Reading is where you might hear the voice of God undiminished by minds higher or better than the one you have. Reading the word moonlight sets off a glow; the word water gives refreshment to the soul, and when they all add up, love stirs the heart.