“I believe, but I do not know with certainty, that I was born in Halifax, Virginia, on February 7 in the year 1812.” Thus begins the current prologue of The Compromise. Otis Greig Roche writes his narrative with uncertainty, instability, and yet with devotion to the land and people of his birth. Like his author, he has found hidden strength in letters.

“There is no record of my ancestry I ever saw, but some write their own histories, mapped out by facts, and propelled by ambition. For others, dreams strain to keep up because there is no permanent safety in ignorance.”

The Compromise, Prologue

Identity and Literacy

In our time, we are usually sure of the basic facts of our birth. People construct identities around families, schools, employment, religions, politics, names, sexes, legal status, and national origins. We are enabled and constrained by these categories. How would identities form in the 1840s with uneven access to institutions and formal records? Otis is enslaved, a shadow to those who enslave him. What constrains him and what finally lets him step out of that shadow? What identities does he step into? What if his enslavers are also his family living and loving across the deepest divides? Here I explore the shape of his character as revealed in the opening of the novel.

Literacy. What does that mean to a man of mixed race for whom literacy was prohibited? One answer is that stories of the young nation could become myths around which he assigns reality. He grew up watching both sets of people. He belongs to neither and to both.

What if his enslavers are also his family, living and loving across the deepest divides?

To see the motivation of one social group, we step out of it. This occurs in margins and intersections. I have tried to show that Otis reads and reasons in one social group and speaks and feels in another. His dual race, the hidden ability to read, and early fascination with rhetoric affects how he functions in his divided and stratified world. “The Boyhood of Otis Roche” begins, set to paper when he is thirty-two. The order of its scenes are determined by Mariah’s story. In braiding, which is the central strand? I am challenged to do each story justice.

Origination Myth

With Otis’s narrative framing the book, I can spin a complex history for setting, theme, and tone. I begin with his father’s world. The embattled new nation survives on the rugged landscape, as idealistic as its youth and unrefined as its hypocrisy.

At the beginning of the novel, Otis stands in for his father and takes emotional and practical leadership of his younger half-sisters. He applies the American myth.

Then Otis stood tall and spread his arms. “This is America,” he shouted with a big grin, “where each day the sun rises anew. There will be no tears today!” He danced a little jig to amuse us.

Otis builds an origination myth for himself. This is a myth of greatness, a hero who faces mortal threat yet survives for the good of his people. The prologue begins with a set of dramatic images, the near-fatal destruction of earthquake and fire.

... February 7 in the year 1812. That was the day of the mighty New Madrid earthquake, the day the steeples and chimneys fell, the day the Mississippi River flowed backwards and sprouted waterfalls at Kentucky Bend. The British burned Washington DC when I was an infant. They said the wind carried ash to dust our hair, and our Virginia moon turned red. I was safe in my ignorance of those events. How different our histories would be if the earthquake had buried the new nation or the Crown had vanquished the new democracy.

My artistic choices imply continuity with the legacies and traditions of American culture.

Contradictory and unexpected events happen, this prologue says. Yet my artistic choices imply continuity with the legacies and traditions of American culture. A sensitivity reader early in the novel’s development advised me that only bad writing was insensitive, and this writing was “not bad.” I took that as a challenge and an invitation to be the writer I am, accepting my position in time, generation, and identity. Mine is not among the voices that have cultural strength, however. I call for patience in an impatient time. I show ambiguity when others polarize with rage. At the same time, I have no desire to force some to make public confessions of brokenness to serve others as a pathway to liberation or vindication. Otis is on both sides and there I find honesty and wholesome work.

My relationship to my character Otis, the activist, has been most affected by contemporary cultural movements, and I continue to be indecisive about using his first-person narrative. This ambiguity is found in the prologue.

Hand in hand, the mortal Enemy and the living God passed by my crib so I cannot know which breathed on me. Human rivers flow by inhuman means, fragile as a newborn and ancient as the world, and still the blood of many continents flows in me.

Ancient as the World

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

Langston Hughes, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”

With unfathomable generosity, Hughes moves his small, piercing lyric from the Euphrates to the Mississippi River. Made irresistibly rich by this influential American poet, the motif is used several times throughout the novel. It begins in the prologue, hopefully in language shaped to represent another inhuman history in which humans find themselves.

“Human rivers flow by inhuman means, fragile as a newborn and ancient as the world, and still the blood of many continents flows in me.”

The Compromise, Prologue

My mother was a slave, as was her mother who, I believe, was brought from Africa and sold to build this country. Some say those first men and women came in the bellies of slave ships as beasts, sent to mine the evils of the human soul. I believe my grandmother was among them, agonizing in hell to deliver my mother, and she delivered me into the New World. We went down into the hell of slavery, but in faith we lived, and in time we thrived.

A typical student of history may neglect life’s mysteries, chains of unimaginable causes and effects. Our forebears’ diligent efforts were repeatedly thwarted. Folk beliefs apply theories of morality, destiny, and fortune. Fiction tries to show a pattern, how to find meaning and connection to our lives. The mystery is also the playground of poetry. I give Otis lavish oracular cadences as I write for him. I am using the great American tragedy of forced migration, its inhumanity, which calls forth the strength of the human soul.

Survival of the single child can be a mystery, yet people are directed by forces as catastrophic as earthquakes. The Middle Passage washed away our histories until we planted them again. Rope pulled us from the places of our birth. The same rope lifted sweet well water to our lips. Ash burned our throats and sealed our lips until our songs of liberation were heard. If the living truth is the greater ornament to our 19th century America, both stories may be true.

The story of escape from slavery has always been a testament to the human spirit, and in its time, the slave narrative rallied abolitionists at public lectures and circulated in newspapers and books. Otis begins writing about his boyhood after reading a call for stories in the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator in July 1840. I have repurposed a few of William Lloyd Garrison‘s phrases: song of liberation, and ornament to society. Contemporary taste may find these phrases patronizing and inflated, but I believe they were inspiring in their time. These phrases show up in the prologue and much later in the novel, the evening Otis and Hester read the newspaper in the kitchen and Otis begins writing his narrative.

Otis straightened the paper. “Listen to this. Mr. Garrison says he wants escaped slaves to tell their true stories, it says ‘from the brutality of bondage to the song of liberation.’....They want men, it says here, ‘needing but a small amount of cultivation to make him an ornament to society and a blessing to his race.’”

“For blessed work, the liberation of our people,” said Hester with a rising tone of happiness.

With the support of his fiancé, Otis writes his narrative to join a social movement forming in opposition to slavery. But looking at The Compromise through a contemporary lens, the narrative is my character’s search for his own story. He is finding a myth in which he can create what he does not have, a story which can hold together uneasy parts of himself. The hellish stories we fear and hide come forth. This psychoanalytical approach to story is based on the ancient heroic cycle. It is through first confronting terror and grief, our beliefs say, that we can heal cultural trauma and systemic oppression. Our current period in America invites us to find our personal or collective myths and hold them to the light. Even so, great caution is required when identifying ourselves with particular histories.

Finding a Mother

The force of mothers and fathers on a child’s moral development was removed to make way for industrialization.

At another level, history is not myth, it is us. The Compromise is a story of mothers, how they change us in defiance of authorities, even when they are taken away and hidden. A man born in 1812 could have witnessed in the life of his grandmother, the end of the transatlantic slave trade, ended by law in 1808, and in the life of his mother, the equally unholy domestic slave trade, and in himself and his children, the generations-long struggle to find personal honor in a system made to remove it. The force of mothers and fathers on a child’s moral development was removed to make way for industrialization. Otis imagines the mother he did not know.

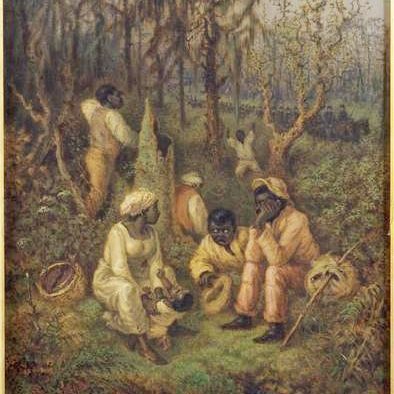

According to the custom on plantations, I would have been weaned and parted from my mother after a year. I have no memory of her, and she would not know me today under any circumstances. I believe she sang to me because I have always been touched by music. I believe she was strong of limb and fierce in disposition. As a small boy, I imagined my mother hiding in the Great Dismal Swamp where she could live free with the Maroons. Alligators kept the slave hunters from coming to get her. And someday, I would find her and set her free.

The Maroons lived outside of slavery in the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia and North Carolina. Though life in the swamplands was true for thousands, with this tale, Otis proves the power of his imagination and strength of devotion.

The child wants to be a hero. Then he must turn to reality in my fiction where he is less heroic and more entwined with those around him.

As I write, I see my sisters with their lives ahead of them. I hope and fear for them and set my pen aside to hear them. From three mothers and a single father, our histories converge.

“From three mothers and a single father, our histories converge.”

The Compromise, Prologue

After the prologue, the three siblings begin their adventure. Some of their ambitions hold and some do not. Many tensions of The Compromise are between mothers and fathers, their incomplete relationships with one another and their conflicting influences on their children. As it was in my family, the children are left to hold their union when the parents are gone. Each half-sibling finds a rocky path to a new family.

By the time Otis writes his narrative, he has lived with the paradox of being of two races, white father and Black mother with separate histories. Each is kept hidden from the other but capable of being found in his life. In my novel, his story is braided with those of his sisters. The epilogue is written in the form of a letter Otis writes to Mariah.

Sometimes I fall silent when I gaze upon my son and daughter because I refuse to mold their futures with pessimism. They who follow must exceed my grasp. The pessimist is caught in a quagmire of arrogance. This I have learned from the errors of my elders. You once told me, “Creativity is the child of freedom. As long as I create, I am free.”