The horses began to pick their way down through rocks and brambles. This canyon, if seen from above, was a crack, he thought, easily overlooked and a good place for those without a homeland or a nation.

Willing yet not so surefooted, I write through rocks and brambles towards what is concealed. It is a descent into what is often hidden in American history, theft and degradation. This is the history, but fiction can thread human experience with multiple and alternative truths.

Otis has followed his guide across the northern plains into an encampment. He has gone to ask for help in the abolitionist cause and to learn about his adopted Cherokee mother, Enola, who disappeared five years earlier.

“She’s gone, and not seen from,” Awi told him. “Not in the territories neither. Plenty lost on the trail though.”

Otis had already accepted this, or believed he had. “Plenty lost along the trail.” It was said flatly against the gush of loss that would have to wait.

Awi rode up close and said, "Someone in Stoneville betrayed her. That's what I think, and the federal agents came and took her away.”

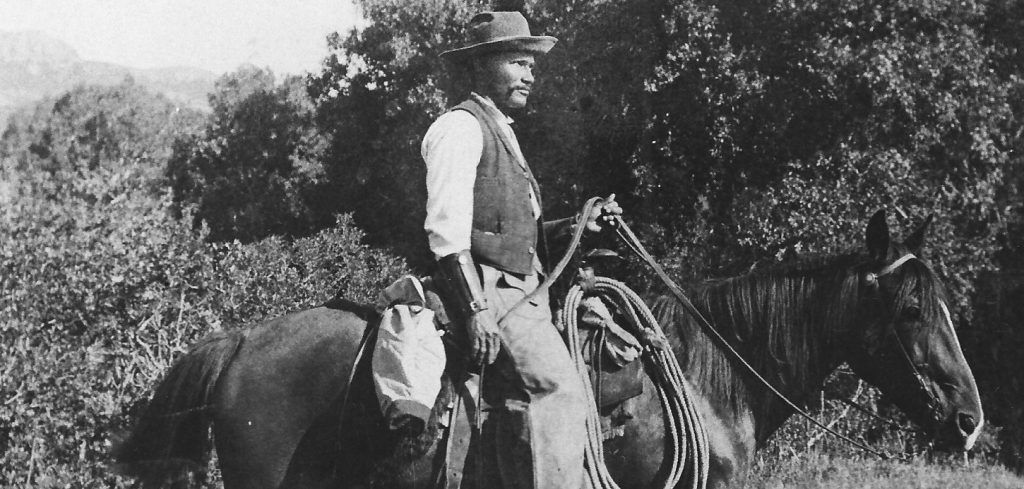

The Compromise, “Otis and Awi”

Enola went missing when the sisters were teenagers in 1838, near the end of federal action, the Indian Removal Act. Land was taken for speculation and homesteading. The people who lived there were driven into institutions or into hiding. Acknowledging the mother’s disappearance is the first major event of the novel. Their white father arranges their futures. How the sisters cope and seek renewal is the rising action.

For many years, the half-siblings don’t understand what happened. Mariah in first-person narration says, “Federal law took her, so maybe federal law would bring her home.” Entering the canyon, the reader meets the possibility that the family was torn apart by someone’s betrayal. The question of who betrayed their mother to the authorities haunts Otis, and his mind is weakened by hunger and sleeplessness.

The trail into the canyon leveled out. Behind the steady hoofbeats was a trickle of water. Then he let himself think of her, Enola, the Mother they had worshiped, and she dissolved into Mariah, her hands cupping water in the moonlight. A doe looked at him before bounding into the shadows. Otis shook his head. Maybe he was in two places at once, and his body could dream right where it was. The trail turned and was lost under him.

He leaned on the saddle horn. Pictures flooded into his sleep. Hester was offering him a plate of steaming biscuits. Embers fell out of the stove and became lumps of dead bison alight with birds. Shadows on the land moved more quickly than clouds around the sun. He pulled his head up to hear the wind rushing between stones....

Would [Jebediah] betray her? Otis felt his chest tighten like a fox crouching.

Rising Surge of Violence

How will this news affect Otis? Maybe the news of betrayal reveals chronic submission and bitterness indicative of oppression or it might awaken the passion of the heart in a surge of liberty. Is there another option? In My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), Frederick Douglass described his fight with Covey as leading to “a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom.” How does a surge of passion propel spiritual or political liberation, the kind described by Douglass?

Many works of art are shaped by the heroic cycle, a descent into death is followed by a purifying ascension. We see this symbolic use of violence in historical novels by Colin Whitehead and Cormac McCarthy. Of course violence in story is deeply human. Raw impulses are integrated into a theory of meaning that we can hardly live without.

Violence in literature goes in multiple directions. Literary critics and philosophers have their say. This world is, to quote Nietzsche, “eternally self creating, and self destroying.” Ancient myths speak of the same turning wheel. Contemporary stories prove that our theories of meaning are alive and well. Critic Josiah Johnson explores violence in the writing of Cormac McCarthy.

“In his texts, McCarthy takes his characters away from the social order which informed their notions of morality and places them in chaotic landscapes where the laws of nature rule. This transition forces his characters to reevaluate their concepts of life, death, and truth as they struggle to meet their needs and fulfill their dreams. Each story is a Bildungsroman culminating in maturity defined by an understanding of the natural order as violent and the concept of evil as an invention of human morality that has no place in the primordial workings of the earth.”

Josiah Johnston, The Function of Violence in Cormac McCarthy: Literary Criticism (2018)

Johnson suggests that violence is part of maturing; the adult sees and grapples with the awful truth. I grapple with what this narrative means for our society. Civil society is defunct in McCarthy’s dystopias, and what’s left is instinct to survive and an impulse to see and speak the truth. Christianity informs this narrative of the transformative power of violence. In the secular version, the artist stands in both worlds and turns towards man’s flaws in order to redeem them. If a writer is doing less, there of less of a writer.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth

The Labyrinth

Going in a similar direction, Joseph Campbell, who began by studying the myths of indigenous people, is known for developing the heroic cycle or monomyth; the hero encounters supernatural forces and wins a decisive victory to return with gifts for his society. Campbell’s comparative study, Hero with a Thousand Faces was first published in 1949. I would have encountered it in the 1970s as well as other works on structuralism in literary theory. I remember watching The Power of Myth with Bill Moyers in the 1980s.

“People say that what we’re all seeking is a meaning for life. I don’t think that’s what we’re really seeking. I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive, so that our life experiences on the purely physical plane will have resonances with our own innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive.”

Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth

I might have learned from Campbell that resonances do the pre-conceptual work of binding the physical and what is called “our own innermost being and reality.” This is where the poet works, through music and image.

We gradually awaken to paradoxes and multiplicities, so there are many labyrinthine caves to enter in our lives. With these possibilities, I am wary of investing in the power of violence. Violence is not an easy fix for social or interpersonal change. Is it too easy to compel readers to turn pages to satisfy primal needs for sensationalism and spectacle. Could we be talking about “men’s fiction” here? This might be too tritely masculinist for me. Can I be true to my male character, his identity development as Black man, and the conventions of the novel while being true to myself?

Some might say that divesting my story of violence is avoidance of the shadow world, the earth itself, or the heroic impulses that push us to evolve beyond the confines of gender. Or is that code for the confines of my gender? The confines of my race make my processes even more labyrinthine.

I have only very recently been introduced to the theory, Nigrescence. Clearly, this theory of Black identity development associated with William E. Cross Jr. can inform the character development of Otis.

The study of nigrescence (a French word meaning the “process of becoming black”) evolved in the late 1960s as observers, especially Black-American psychologists, tried systematically to map and codify the identity transformation that accompanied an individual’s participation in the Black power phase (1968-1975) of the Black Social Movement. First and foremost, this literature is important to students and scholars of Black identity because it offers an inherently more complex perspective from which to frame discourse on Black identity.” (p. 147)

Shades of Black: Diversity in African American Identity, “The Psychology of Nigrescence,” William E. Cross, Jr., 1991

By the end of the scene in the canyon, the story takes a turn which is influenced by my readings of Shades of Black and Malcolm X: In our own image, especially the writings of Cornel West, which should be explored in another blog post.

Vision Quest

The scene which takes Otis into the canyon begins by describing the mystery hovering near a harsh reality. It is a vision quest that shapes his decisions going forward. Here I might individuate my characters and inspire a “better” outcome for the novel, but clearly, my creative urges go in the direction of giving life, not taking it in acts of bravery or vengeance. If this causes me to lose male readers, so be it.

They picked their way over stones and rode into the mouth of a cave about twenty feet deep. It was cold and lined with red and black stones. Awi stopped his horse and lit a match. Otis looked up as the light moved over the deep red stone above. It caught dotted shapes, a deer’s cloven hoof and the four-pointed fox print. He could not be sure, but around the prints was the etched outline of a face in profile, her face, Enola etched in stone.

“Was she here?” he asked. The light changed. It looked more like the head of a bison.

Awi shook his head. “Look and you might see something. In the old stories, this is where Buffalo come out of the earth.”

A hum of history underlies experience.

In writing these scenes in the canyon, I am indebted to Gaylord Torrence, scholar of Native American art.

“Hoofprint Tradition rock art, produced primarily by women during their vision quests, is also closely related to nineteenth-century Plains Indians…. the caves were revealed as the “Home of the Buffalo,” where Bison were believed to emerge periodically from the underworld to replenish the herds that people relied on for their livelihood”

Gaylord Torrence, The Plains Indians Artists of Each and Sky (2015)”Rock Art Traditions” p. 58 (Folio)

Reading his commentary reminds me that there are endless stories to be told, and many should be told by those whose knowledge is greater than mine.

The trail into the canyon leveled out with enough light to see golden-white limestone layered with sparkling gray. The earth takes its time, thought Otis as he entered the canyon’s labyrinth.

One of the theories evolving as I write is that a hum of history underlies experience. It is a history of resilience as much as loss, deriving from powers that are naturally alive in us. It says that heroes are not born out of the sides of gods or from stars as the myths would have us believe. In my humble world, visions and powers do not descend from the supernatural or from biological ancestry. They are not only realized through destruction. They are layered into our 21st century daily lives through the inspired and diligent work of communities, parents and teachers, and all the rest of us. The death of a soldier in Ukraine is not the death of one person, but the ruination and devaluation of those layers constructed over generations, and if one has the eyes to see, over eons of planetary life. That devaluation has severe and deeply troubling aftershocks.

There are volcanos, earthquakes, and glaciers shaping the land. Then there’s water, its slow and steady layering and its slow and steady revelation of what came before. How will I find a dramatic story of identity development under the conditions of oppression, not violence?

Hidden Canyons

Soon after the investigation of the cave, Awe leads Otis into the canyon encampment where there is a small community living together in exile. Writing this scene I am, of course, influenced by personal experience. In fact, I lived much of my childhood on Hidden Canyon Road. Ours was the last ranch house nestled among hillsides of terraced fruit orchards. I had the privilege of belonging to this place with a jacaranda tree, an avocado orchard, orange, peach, and fig trees, and several horses, dogs, and chickens. I had the rare 20th century privilege of feeling at home among hills explored on horseback or scrambling across creek beds to find wildflowers or follow deer tracks. It was common to see deer, fox, coyote and rabbit. I ate wild berries and fennel seeds. I found fossils, one arrowhead, and a snake skin. I was never afraid to be alone in these foothills of the San Gabriels. I found deep subjectivity, a state of mental freedom I frequently give to my characters. However, I did not think that the history under me included the Gabrieleño or the Kizh people. Nor did I recognize that the red burns under the dust on my on my ankles were probably caused by contamination. The Union Mattel Oil company started drilling under Los Angeles in 1865.

Though Enola is gone by the novel’s opening, her influence is in every moment of subjective experience. This is a valuable freedom, I claim, that love and security provide against the actions of those who can divide us from it. This gives rise to conflict in my fiction that is very real to me, but I must continue to imagine how my character Otis experiences the world as an enslaved Black man who has also tasted richness of ideas and language as well as the love of women. This scene might be the turning point the novel needs.

My knowledge comes from observing people who hide to survive.

The canyon in the scene is also influenced by the encampments I saw in San Diego, California. Those canyons were inhabited by people who had crossed the border and needed to survive for a time without homes. They were canyon dwellers who sheltered under the trees and cliffs behind large houses with manicured yards and swimming pools. Yet, they were the people who manicured the lawns and cleaned the lavish interiors. They were too easily “disappeared” by mainstream society because of their legal status, physical characteristics, and languages. Being a young ESL teacher, I saw them take risks to enter our school. They frequently disappeared and reappeared after weeks, possibly having been in detention and crossing again. I hope I gave language lessons to them with kindness even when I was too naive to understand their precarity or my privilege. I was not only an outsider dedicated to their acculturation into low-wage employment. I was also acculturating into their lives to some degree. Teaching goes both ways or we are dead to the world. Otis, too comes to this encampment as an outsider who is curious and alert.

A dog barked in the distance and was stilled, so they knew he was coming. Otis could smell a wood fire, tobacco, and roasted corn that made his mouth water. A baby whimpered inside a wooden hut. The soft sounds of women fell silent. He felt their gaze. He found a place for his horse among others barely lit by a campfire under a canopy of creaking trees.

Men and elder women squatted or reclined near the warming fire and welcomed him.

Lost Generations

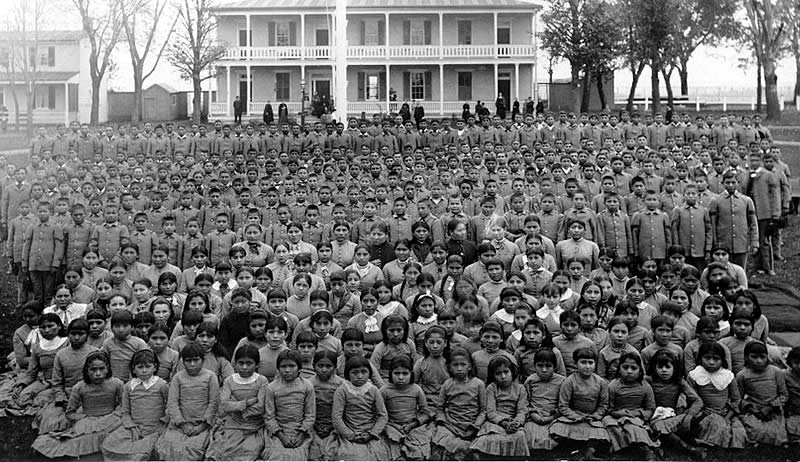

I try to tell a complex story in the canyon, not only of proud indigenous ways but of vulnerability and resilience on the land during this decade in history. According to historical accounts available to me, the Osage and other tribes of Missouri had lost their ancestral lands by 1825, thirteen years before the opening of my story. American Indian residential schools were established starting in the 17th century. Many residential schools were operating west of the Mississippi, though possibly not in Missouri, in the 1820s and onward. Later in the century, the government compelled the native people to give up their children in exchange for food, and treaties had clauses trading schooling for land. The boarding schools encouraged agriculture, but this economy left the people more vulnerable to the spread of disease. While the history of intervention and forced acculturation is distressing, the statistics about how many indigenous people died in epidemics, cholera and smallpox, are even more harrowing.

Visit The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition site.

I have no clear evidence of exactly how or where significant numbers of native people lived in 1840s Missouri. I guess they survived by hiding or passing. More research is in order. There is plenty of evidence, however, that native people and Blacks who escaped slavery lived together. This precious legacy is found in our ancestries and family oral histories because the people and the stories endured.

Light had filled in the clearing. Otis saw the people, nearly three dozen. They were all different from one another, light and dark, large and small. He guessed they were Iroquois and Osage, and others who blended their languages with English and French. A few who had the skin color of Africa questioned him with their eyes. He knew that to them, he was a mulatto with the angular brow and whiskers of an enslaver’s son. But the majority were original people. They wore cloth woven in Eastern factories and homespun with woven stripes. The symbols of their tribes were different as well, with meaning that he could not read.

Historically, the land determines the means of production. How openly and with what viability we live on the land and with one another forms our characters. Our identities seems to endure until our physical relationships change and we are lifted into a different reality.

Primitive Masculinity

“A terrible remedy for a terrible wrong“

I am also influenced by my research, specifically, John Stauffer‘s book, The Black Hears of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (2001). His chapter called “Learning from Indians” describes how major abolitionists used the symbols, not the reality, of native people to inform their methods. These included an ideal of “primitive masculinity.” It allowed them to idealize the rigors of the wilderness and violence in the cause of their spiritual crusade. John Brown believed it was right to kill defenseless men associated with slavery. Brown and other abolitionists employed “a terrible remedy for a terrible wrong” and repeatedly called on the romantic images of “brave Indians” to inspire them. These images, Stauffer claims, were stereotypes even though some white abolitionists were personally involved in the lives of native people. Evidence suggests that native people had become curiosities of the past, but this is a story I resist.

Such stereotypes support the cultural insensitivities that editors and critics confront today. To a knowledgable and sensitive reader, they sound like cliches and platitudes, and I have routed a few from my imaginative world. It is better to stand in awe of the unknown and take one step at a time. However, I am still deeply influenced by romantic notions of the sacred that cannot be easily replaced by a more “authentic” experience. When I was not roaming the hills, I was reading Romantic poetry and playing classical music on the piano. These ideals inspired me to become a teacher and writer. These same notions of spiritual freedom and equality under God compelled the transcendentalists to become fervent abolitionists. Stauffer discusses the abolitionists interest in the revolutionary fervor of the poet Lord Byron. My family brought me up to question authority and think in poetry; I cannot betray that.

Though I have shared the peaceful and life-affirming Transcendentalist influence on abolitionism, some abolitionists believed in the regenerative power of violence. Garret Smith, according to Stauffer, “invoked the Great Spirit of the Indians to help make him brave.” My fiction descends into a parallel telling of radical abolitionists, which is situated in my own life and times and my struggle to find an alternative truth in fiction.

Cracks between Worlds

“Patience is the road you take to your demise.”

It is therefore daring of me to represent in this novel how some indigenous people may have lived in hiding and also engaged in the issue of slavery. The people would certainly not be limited to romantic symbols from a white European perspective. Would their perspective radicalize Otis, to rationalize revenge? Or to broaden a liberal mind. I can try to imagine these narrative possibilities with nuance and complexity.

I rummage in my known world to depict people who have lost their lands and languages, were left behind or escaping wrongs, and then come together temporarily out of the need for shelter and human kindness. I return to the hidden canyon to find an anguished voice, vulnerable and proud, and I give perceptions to the limited third-person narration of my character, Otis.

Some wore the garb from government schools over woven tunics and leather leggings. This he understood. These were the lost sons and daughters, taken to be educated in government and mission schools. They spoke the white man’s tongue and inhabited cracks between worlds. They were dreamers like him, passing through, filling in with notions of a better place.

Otis receives their generosity and sees their material conditions. They lack sufficient water and soil. They can’t support their collective through the winter. They are losing their young and their languages. Even so, they urge him to defend his manhood and not wait for acceptance in white society.

“Patience is the road you take to your demise. We know. We took their road and now we live in the cracks of the earth like ghosts.”

“The young leave and forget our ways.” It was a thin brown woman across from him who spoke. “Our words will be no more. When the water sickens and dies, we cross over, and it is right to go.”

Otis nodded and had to pull his eyes from hers, veiled in dry skin. Her eyes had also said that they could not feed their people in this canyon. If too many ate their stores, they would weaken and starve come winter.

“First take back your manhood,” said the one whose white hair caught the only ray of sun. “Before they make you into sheep and you fall sick. Then you can look for balance, what your people call freedom,” the old one said.

Otis feared the sadness welling up in him. In this moment, he could fall silent or prove his strength for the cause. “Will you help us? Ride south with me to Columbia. Join our Brotherhood.”

The scene closes as two men from the canyon go with him back to Columbia. These two men were educated in government schools and pass as white. They help Otis ferry people out of slavery and quietly influence the story. I try to show that some among them entered a different society with intention and integrity.

The two men nodded and pointed at their horses already saddled. “We’re ready to start something new. Riding out to free people and starting towns, sounds right to us. We’re done hiding and going nowhere, right Fred?"

“Halfway between nothin’ and nothin’ is still, you know.’” Fred was the quiet one.

“I say all folks have a natural right to the soil. Like life and liberty. I’m Jake, and this’s my cousin Fred. We know the way to Columbia.”

Otis is a man of mixed race, raised in slavery, literate, and influenced by an adoptive Cherokee mother and a white father. Multiple stories result from the basic premise. Like a hub, there is a still center in the fictional present, and like music, the beat rises in and out. Enola stepped away from her people to raise Jedediah’s children until she was stollen. Fred and Jake leave their fragile connection to their tribe. They work and start families with goals and beliefs. The hum of history underlies their experience too. Mariah loses her independence to raise a family that, in theory, became my own. If I inherit her tragedy, I also inherit her resilience and her humanity. How many of us stepped away from our roots as an act of love only to find our taproots more deeply alive?

“I say all folks have a natural right to the soil. Like life and liberty. I’m Jake and this is my cousin, Fred.”