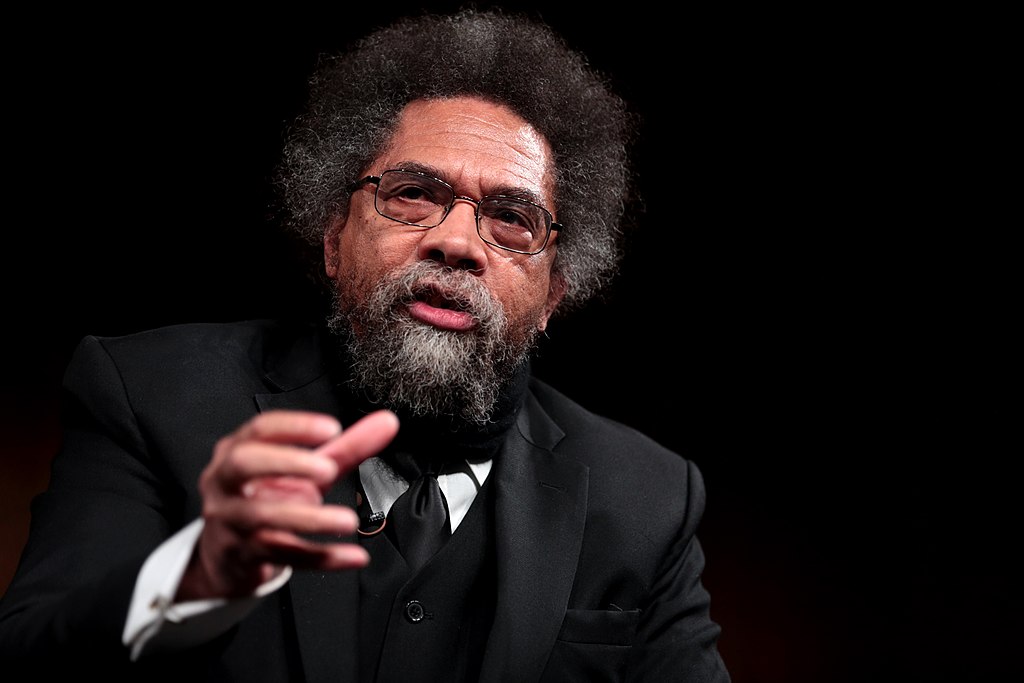

“How does integrity face oppression, how does honesty face deception, how does decency face insult, how does courage meet brute force?”

Cornel West, 2021

“How” questions guide qualitative research, fiction, and philosophy. No single idea could answer such questions as those posed by Cornel West. If there are answers, they are in a pattern of speech and action, in a life situated in the precious time and place each of us has. Traces of those patterns are what I seek as I write The Compromise.

The story of a young enslaved man maturing with conflicting loyalties parallels the nation’s story of slavery and abolition.

My characters come of age as they grapple with their place in society, seeking integrity and belonging while mired in vast injustice and oppression. That historical “place in society” we might see more clearly from our time, but it is still a difficult story to tell across race, gender, and social class. Mariah learns to face insult with decency. Eliza tries to use deception to reconcile ideological discord even before her greatest injuries. The story of Otis’s radicalization unfolds over thirty fictional years. The story of a young enslaved man maturing with conflicting loyalties parallels the nation’s story of slavery and abolition.

Collaboration and Radicalization

“Only by changing perspectives, listening to multiple voices from different social groups and vantage points, it is possible to understand how racial identities get defined, blurred, and remade.” -John Stauffer

Two important books have informed my story of abolitionists: The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (2001) by John Stauffer and The Abolitionists Imagination (2012) edited by Andrew Delbanco. These books are rich with multiple and conflicting perspectives, which I can translate into dramatic action and dialogue.

Abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates in the first half of the 19th century typically believed in peaceful systemic change until they met pro-slavery violence. Events like Nat Turner’s violent revolt radicalized the pro-slavery south. Some abolitionists, notably James McCune Smith, Gerrit Smith, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown lost faith in the ability to correct the path of the country through nonviolent means. They defied the Fugitive Slave Act. The country slid toward Civil War, divided by religious beliefs, ideological positions, and revolutionary passion. Were abolitionists reckless zealots or courageous reformers? Writing fiction, I can aim for paradoxical situations and let the reader feel the pull of sympathies to answer that question. However, every linguistic choice is more or less unconsciously embedded in my own 20th-21st century sympathies.

As a result of their precarious circumstances they began to search for a more secure and enduring reality. They turned away from the structures and values of their material world, on which they could not depend, and started to give greater weight to their spiritual visions and passions of the heart, thereby initiating the process of self transformation that would ultimately converge in their identities as Radical Abolitionists.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men (2002)

The Compromise tells the story of Otis’s radicalization in several settings. In the winter of 1841, Otis, still enslaved and hired out, sets on a new course of interracial collaboration and radicalization when he meets Prof. Kerney and Mr. Meriwether at a dinner party. Our fictional white abolitionists contend with issues of the day, particularly within their own ranks. Prof. Kerney calls for practical humility and warns against extremism in anti-slavery work. Mr. Meriwether disagrees.

Meriwether smiled. “Ah, you counsel plodding social change through endless self-examination. More ambivalence. What we need is a strong vision, not more compromises. The Prophets do not fear for their lives. Neither should we!”

Otis felt a thrill pass through him, a bond with Meriwether.

The Compromise, “Otis and the Columbia Abolitionists”1841

Meanwhile, Otis struggles with his own habits of silence and then speaks words that change his future.

Otis felt tension rise in his belly. Every breath is a compromise.... These men had never felt the violence at the root of slavery. If he joined them, he might try to forget his own history. On the other hand, he might be the one mired in his own silence.... He kept his eyes on his torte and spoke in a low voice. “Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin. Hebrews, chapter 9, verse 22.”

“Ah! This man agrees with me,” declared Meriwether. He pushed back his chair to stand and raise his glass.

The Compromise, “Otis and the Columbia Abolitionists” 1841

That night, Otis is initiated into one brotherhood where he will prepare to enter another, the Knights of Liberty, a secret fraternity of former slaves organizing for armed rebellion. I expect that these fictional events will remind readers of more events in the history of civil rights.

“I feel that I am a citizen of the American dream and that the revolutionary struggle of which I am a part is a struggle against the American nightmare.” -Eldridge Cleaver (1935-1998)

“Others will feel the force of our sacrifice…. Laws change one fist of fire at a time.”

Means and Ends

Our siblings take different paths in The Compromise. As brothers and sisters often do, Otis and Mariah disagree on the means to achieve abolition. In the moon-lit garden, they argue about the boycott methods of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Years later traveling on a flatboat with contraband rifles and gunpowder, they argue over whether the ends justify violent means. Ready to sacrifice, Otis says they do.

“The ends justify the means, Mariah. Others will feel the force of our sacrifice. It’s called freedom. Why can’t you understand that?”....

I felt confusion tying up my insides. In a way he was right. In another he was wrong. I walked in a circle one way and then the other.... At last I said, “You used to believe in changing the law. You said it a hundred times.”

“Laws don’t start inside Congress. That’s not how things work. Laws change one fist of fire at a time.”

“Wait, Otis. You have to wait for ‘one man, one vote.’”

“No. I’ve waited long enough. I’m not doing this work for myself, and neither should you. Keep your eyes open, and remember what’s important.” He looked away like he had the last word and the conversation was over.

“Look at my hands. These bring life into a land worth living in.”

“Worth living in for whom?” he asked. “It don’t include me, never did.”

My voice was shaking with anger but kept going. “There’s wisdom in keeping us alive. This’s what I know, and you don’t need to agree with what I say.”

The Compromise, “The Work We’re Doing” 1845

Mariah vows to help her brother, but navigating a difficult compromise, she also holds her ground. A similar dilemma is faced by activists in our time who conduct nonviolent protests that turn violent. It is faced by those who go to war for a cause they believe is just. There are many such compromises when social goods compete. People of integrity struggle with their rights and freedoms, then as now. Integrity can be blindsided by those who think it lacks strategy.

“To me, the thing that is worse than death is betrayal. You see, I could conceive death, but I could not conceive betrayal.” -Malcom X (1925-1965)

Jailhouse Yard

By the time the story finds Otis is in the jailhouse yard, he is being tortured to reveal the names of his conspirators. In the words of Cornel West, he meets brute force with courage. This theme is well-known in our culture. He endures pain to protect the brotherhood and the others who rallied to help him.

A jailor kept whining and pulling the chains upward. “You gotta name names ‘cause we’re cleaning up all the loose charcoal in this town."

After excruciating dislocation of his shoulder, he lies alone in the freezing cold and slips into a lucid dream which takes him back twenty years to resolve a mystery. The original injuries to his shoulders and legs occurred when he was attacked by a group of boys of mixed race. Each group had reason to hate him, envious sons of the slave owner and angry enslaved workers over whom he had cracked the whip. They attempted to draw and quarter him resulting in permanent injuries and emotional scars.

“He gets what he deserves,” groaned Woodie as he yanked on one leg.

More young men came from the field, those who envied his boots and felt his lash that morning he started as overseer. They drew and heaved until both his shoulders broke. One boot slid off, which saved his leg. Woodie and Nape let go of their ropes. Otis’s face dragged and broke on the rocks. A bright sound cracked. The dank air gushed and sloshed like water. He was coming up for air.

As a grown man and a member of a fraternal order, Otis has the chance to understand the tragic event in which two sides collaborated briefly to destroy him. He reenters the past from the precarious present. But Otis is not alone for long. He sees a man come over the jailhouse wall.

The city’s gaslights outlined the curved wall topped with broken glass. The darkness moved. His eyes rolled up to see a big shadow crook its way down the wall. The whimpering stopped running in his head. “Shoulder out,” he murmured.

A boot came down on his right wrist. “You shut up.” He knew that deep voice and didn’t need to see the face seven feet above him. It was Boswell the Nigerian, the Commander Knight of the Brotherhood, come over the jailhouse wall to save him. “An’ stay shut up,” he said. It meant, No amount of pain will make you talk.

The Compromise “Jailhouse Yard” 1846

Boswell of the brotherhood comes over the jailhouse wall. Their plan to deliver arms has succeeded. The modern reader might hope that Otis’s divided psyche becomes whole in this scene of brotherly love. Healing humanity within himself, he might heal his trauma, or said another way, he may seek instead peaceful and effective means to secure human rights. The answer could be an interpretation of the biblical reference, “The bush will burn.”

Boswell, the strongest man in St. Louis, pulled Otis to his knees, cradled him from behind, then gripped his left arm above the elbow. Otis took his jolt and the bone went into the socket. The scapula grazed his ribs and he crumpled with pain. “The bush will burn,” Otis whispered.

“If the Lord comes and burns – as you say he will – I am not going away; I am going to stay here and stand the fire, like Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego! And Jesus will walk with me through the fire and keep me from harm.” -Sojourner Truth (1797-1893)

Standing Back

“[I] consider the abolition movement as an instance of a recurrent American phenomenon: a determined minority sets out, in the face of long odds, to rid the world of what it regards as a patent and entrenched evil.” -Andrew Delbanco

How does one adhere to the truth within oneself when that truth is in conflict with the truth of those who hold more power? Radicalization seems likely if not inevitable when power is abused. The deep insult of human enslavement, it seems to me, is not only the threat and the indelibility of physical violence, but the division within the psyche caused by chronically unfulfilled yearning to be treated with dignity, free of debilitating social control.

Rage is a natural effect of this unfulfilled yearning, and it may seek to reinforce itself. Abuse of power through unreasonable social control appears to be another addiction. There must be points of intervention. Kathleen Belew, professor of history at the University of Chicago offers advice, which includes better public policies and teaching of history. Educators and other public servants need resources to apply what does not polarize or exclude.

Passion for engagement in society can, I hope, mature into political organizing. A functional democracy makes way for peaceful collective action and collaboration. The Black Lives Matter movement says, “With Love, We’ve Changed.” And so the story comes full circle with this simple and clear answer to Cornel West’s series of “how” questions. Love.

“How does integrity face oppression, how does honesty face deception, how does decency face insult, how does courage meet brute force?” -Cornel West