This post on The Compromise began in February, 2021 when the two half-sisters’ narratives started working together. Eliza stepped up as a point-of-view character told in the third person. This followed the advice of the Reedsy evaluation editor. This additional POV character provides more psychological tension in the family. The family. This is, after all, the very place where we begin to unconsciously reproduce social ills or challenge and transform them. No small concern, these issues of character also determine the novel’s structure. Will the protagonist overcome her shadow-side antagonist, or do we have a braided narrative in which each has her own strand with an inner shadow and each finds her way to adult consciousness?

Image: The Travelling Companions, 1862. Artist: Augustus Leopold Egg. Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust on Unsplash

I have spun my wheels with the pros and cons of a classic antagonist. Emphasizing the sisters’ contrasts could be overly simplistic, the vile making the virtuous seem more virtuous. Asking the reader to hate one sister and love the other would be writing like a bad parent. Is there anything more troubling and ubiquitous that sibling rivalry? I might encourage their rivalry to serve my need for drama. There is a psychological correlation. Conflict and rivalry push us towards conscious maturity, towards individuation.

“We need to be more than brave, self-sacrificing Heroes. We also need to be Virgins who bring our inner talents and self-fulfilling joys to life. And we need stories that show us how to do that.”

Kim Hudson, The Virgin’s Promise, xxv

The fulfillment of a female self, I reason, could not be empty of sisterhood. I remember the 1970’s feminist anthology, Sisterhood is Powerful. If the bond of sisterly feeling is unbroken, this would be a story of the fight for solidarity against the divisive world. Then external forces would separate them with more pathos. That would make female rivalry less necessary on the path to self-knowledge, at least for those who grew up without sisters. What’s more, centering “women’s fiction” on female rivalry could narrow my audience. Male readers might lack the motivation to engage with the tension between sisters when it relies on envy. Young readers might prefer spunky, athletic heroines who leap over mountains to save their societies. I also feared that following Eliza into a brothel meant leaving the Young Adult genre. Tried-and-true approaches to storytelling turned into a jungle of concerns.

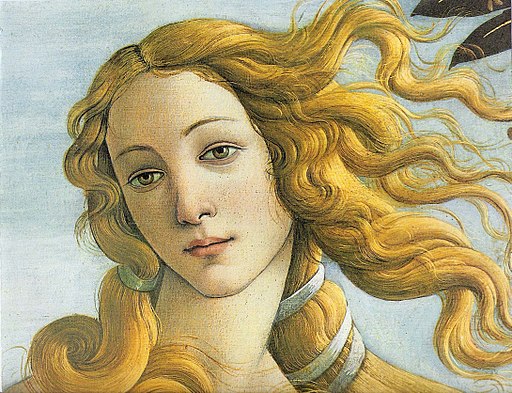

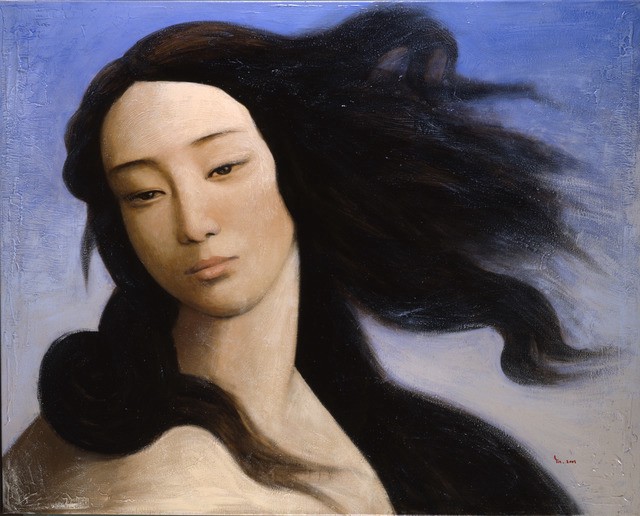

The Virgin and the Whore

Mythic structures might help to hack my way through, pardon the pun. Kim Hudson (2009) wrote The Virgin’s Promise, a book to encourage storytellers to use female archetypes and to respect the beats, the plot points, of a journey towards self-knowledge. The female archetypes, realized by any sex, are significantly different from male archetypes, this theory claims. Male archetypes are seeking “external adventures and physical challenges.” Depending on the novel’s ending, Otis is such a hero. Female archetypes favor relationships, the experts say, which throws a different light on our cultural ideas about storytelling. Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, wrote a forward to The Virgin’s Promise, where the authors differentiate the male and female archetypes.

“The female heroes seem to move inwardly towards the center of a series of rings that represent the different levels of female relationships – relationship with father and mother, other women, men, children, society, the gods and goddesses, and finally at the center with themselves, their own true natures. Then they may return through all those levels, unwinding the spiral, applying what they have learned at the center to each set of relationships.” (xiii)

Christopher Vogler, Forward to the Virgin’s Promise, xiii

While this is an excellent concept and depiction of a labyrinth, I am not sure that it describes the current structure of The Compromise. Can it be about the compromises we make along the way, balancing self and other? If there is a center, it is discovered and expressed as we live and learn, much like the return journey of the basic image Vogler describes.

Our two characters, Mariah and Eliza fit easily into Hudson’s rendition of the Jungian archetypes. They are figured as a cultural trope. Seen in this light, Mariah, the wonderful Virgin, who uses her talents and fulfills her dreams, is opposed by her shadow character, Eliza the Whore. To Hudson, this terminology is not moral stricture. Hudson writes, “The Whore feels victimized and loses her autonomy to the control of others and their fantasies”(6). This is a shadow archetype, and I bet many of us recognize her. It is hard to know when one’s urge to please others crosses the line towards giving one’s power over to them. This is office politics. This is a marriage. One’s life could be spent exploring and negotiating this boundary. It becomes violent when it is not negotiated, as in abuse and oppression. Then people need pathways out.

“The Whore feels victimized and loses her autonomy to the control of others and their fantasies.”

Kim Hudson, The Virgin’s promise, p. 6

Loss of autonomy, ironically, begins for Eliza when her father sets her apart for being pretty. Being special can be empowering and yet cause dependency on the systems that proclaim our merit, our specialness, weighed and measured. Authoritarian systems, attractive at first, can be feckless and irrational. Eliza is on such a slippery slope.

He said, “My little Lizzy, you have a gift that will give you angels. And you have something else that will give you riches someday, bright pretties for a chance to look into your blue eyes. And when I have a place in heaven, and if you are very good, you’ll get Otis-boy as your helping hand. That gives you a place beside me where no other girl will do.”

Eliza becomes enthralled by the patriarchy and the fantasy of white superiority. Through a strange twist of fate, this entitlement enslaves her brother. She decides to invest the symbolic capital of her beauty and talent, a reasonable plan for a girl of 16. The reader may hope that the patriarchy will protect her, as it has been known to do. Society was investing heavily in fathers and husbands. Early feminists were not seeking the vote or higher education. They were seeking ways to gain custody of their children. The temperance societies worked to end the drunken abuses of fathers and husbands. There were few safety nets in the 19th century, few legal systems to catch us. We might hope that ambition and hard work could give women a better future. Eliza strategizes.

It was the natural order, everyone agreed. Pretty things had to be kept special. Eliza Roche was a white girl and special among all the others. At this new place, she would become a lady, not a maid. Looking nice was the most important thing. That meant how she appeared at all times. She could sing, of course. She must make friends. Her friends would help her rise into society. It would be natural like a bluebird learning how to fly from the highest branch. She already had a lace pinafore that looked better on her than anyone else. They all said that she was so much better than a chambermaid.

Perceptions of superiority are culturally embedded in multiple layers of identity formation, significantly, involving the status of our work. Survival in American capitalism can lead to, if not require, the oppression of others. Eliza must manage domestic work from a superior position.

Eliza looked out her window to the backyard. The clothesline near the chicken coop was full of rags. Her sister would do it for her, empty chamber pots and launder the rags. Her sister had always done hateful, dirty work like killing animals and cleaning up when people were sick. Mariah had that darker color to her skin and straight black hair that marked her as a primitive. It looked like that girl Hester was going to give Mariah the dirt to clean up anyway. Eliza could put things back when they were clean. That was a kindness, so no one could say she didn’t do her work.

It is no easy task to deconstruct systems of oppression on which our identities depend.

As I deepen awareness of my characters’ motivations, I enable a cascade of experience from their small beginnings. This includes the social construction of race. Though the half-sisters were raised side-by-side, small differences in their experience, including how they appear to others, have lasting influence. Both of Eliza’s fictional parents are white, Scottish and French. At the discretion of her father, as an infant she was separated from her mother’s household, a brothel, and raised by a Native American stepmother beside her half-sister, Mariah. She inherited characteristics from her biological mother, physical beauty and musical talent. Perhaps she also inherited tendencies towards narcissism, magical thinking, and addiction.

In terms of development, Eliza is moving from adolescence into adulthood in the 1840s, a time of increasing urbanization and authoritarianism. There were very few opportunities for women to seek work outside of the domestic sphere, and she was influenced by Scarlett, an headstrong young woman from a higher social class. Educated women had ideals without practical opportunities. The transition to an arranged marriage is fraught. She escapes a treacherous brother-in-law and a passive husband by entering a brothel run by a relative.

We know that a young woman is influenced by complex factors: social, biological, genetic, and environmental. How does one research all this? There are facts of history, such as the use of particular drugs and the number of legal brothels in St. Louis. For women, many situations are part of ongoing reality, such as Eliza’s poverty, isolation, and unwanted pregnancy.

“A working imagination is research.”

Robert McKee, Story (1997)

Braided Narrative

“Requires the recognition of different, often opposing, experiences.”

Corinne Bancroft. “The Braided Narrative” 2018

Eliza’s story typically delivers ethical bombshells. While Mariah is learning to read from a feminist, Eliza is learning to entertain and serve wealthy white girls. While Mariah is delivering babies as a midwife assistant, Eliza is performing in a brothel. While Mariah is traveling to help her sister, Eliza is running from her in shame. The half-sisters’ two story worlds might stay in tension through a technique called braided narrative. Corinne Bancroft wrote “The Braided Narrative” for the journal Narrative. Bancroft says this technique asks the reader to do the “ethical work that requires the recognition of different, often opposing, experiences.”

Many contemporary novels feature multiple narrators who tell distinct, sometimes incommensurate, stories…. I argue that this technique actually constitutes a new subtype of the novel that I call the braided narrative. In braided narratives, novelists plait together different narrative threads, distinct in terms of both narrator and story, to grapple with both the poignant fissure that fractures the most intimate attachments between individuals and the chasm that historical violences carve between social groups.

Bancroft, Corinne. “The Braided Narrative.” Narrative, vol. 26 no. 3, 2018, p. 262-281. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/nar.2018.0013.

A braided narrative may call forth an intersubjectivity to be enacted by the reader, but in the traditional sense, my characters are protagonist and antagonist. The antagonist functions to strengthen the emerging moral development of the protagonist, not the the moral development of the antagonist. I don’t know yet if a braided narrative changes this dynamic. In any case, the reader should see interpersonal fissures emerge and grow. This may describe the illusive feature of good writing, “tension.” The difficulty of maintaining tension among my various characters is considerable.

Bancroft points to another reward of the braided narrative, to let us see the “historical violences carved between social groups.” She says that these are chasms, not fissures. The braided narrative may let the author show the chasms to the reader while keeping the characters blind to them. Without the distance, the story world could be too small to hold the attention of some readers, including me. This could be the weakness of the single narrator common in novels for young adults.

“A braid of stories meant to heal our relationship to the world.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (x)

Narrative helps us see and apply theories of cause and effect related to micro-aggressions or social violences. The act of reading or viewing a braided narrative could provide healing. This is what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls for in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (2013), “a braid of stories meant to heal our relationship with the world” (x).

The Whore and the Virgin

“She was made for greater things.”

The Compromise, “The Gamble Library”

The reader may determine if or how Eliza cooperates in her victimization as a high-class sex worker and where that leads. This complexity as well as the graphic nature of the scenes in the brothel, move the novel away from youthful readers. I have cut several thousand words and scenes from the brothel. I am revising the character Clancy, the Portuguese castrato, who gradually became Eliza’s nemisis. The greater tension should grow between Eliza and her sister Mariah.

For a time Eliza abuses her privileges and manipulates others. She is lulled by drugs, isolated, trapped, and overpowered by brute force. She becomes pregnant and is unsure of the father. She seeks an abortion and acquires flowers that cause hemorrhage, but she fears pain and death.

Eliza nodded and continued to sweat and blush. “Bloodroot is the right name for it.”

Aromé continued. “The purple flowers are pennyroyal.”

“Even pennyroyal? I never knew that.”

“It kills little flies that no one wants.” Aromé pointed to Eliza’s protruding belly which caused her to turn away and whimper.

The old woman shook her head and spoke at length. Then she produced a knife from the folds of her skirt and cut a sprig of each plant except the bloodroot.

Aromé took the cuttings and pressed them into Eliza’s hands. At the same time, Aromé kissed her cheek, which caused Eliza to cry. The Romas curtsied and left her alone holding a nosegay of poison.

The Compromise, “Pharmacopeia for Abortion”

Eliza had a very weak grip on her own autonomy. These plot points do not require historical research to understand. Through her suffering and shame, I have given her voice and a personhood with subject status. In confinement, she is briefly reminded of her own virginity, symbolically the gift of artistry and vulnerable humanity. These should never have been taken from her. She reevaluates her current place in society. Then she wisely reaches for her sister, who never let her go.

“The Virgin may also embody the belief that there is a piece of the divine in all of us, such as a dream or a talent which is brought out by the actions of the Virgin.”

Kim Hudson, The Virgin’s Promise (xxiv)

In the current draft’s ending, Eliza finds her piece of the divine. Kim Hudson says that “Coming of Age [stories] depict the first sexual experience, a metaphor for becoming an independent person by bringing an inner desire to life” (xxiv). This is a worthy ambition for our development. How many systems must be in place to allow this to occur? Sex can give expression and intimacy or children and hope for the future, or it can steal bodily integrity and even cast us out of society. For so many, sex and pregnancy lead to mortal threat, financial insecurity, dwindling options, and extended dependency. It takes real work in every society to create paths that redirect from these threats. And yes, as Hudson says, “we need stories to help us do that.” In the current draft’s ending, Eliza’s inner nature directs her. That nature is self-sacrificing and brave and a piece of the heaven on earth. The reader will have to determine if it is tragically withheld, divinely granted, or forged in our hands.