Political history became a driving force, not background to my story. Curious at first, I expected The Compromise to fictionalize my lineage through its cultural and psychological past. By going back an additional generation, behind the evidence I expected to bring to bear, I found that painful U.S. history had to be reckoned with: the enslavement of people of African decent, the theft of indiginous peoples’ lands, and the oppression of women.

My characters are often caught in these forces and resign to live in small spaces of personal freedom. However, I want the novel to show that moral acts are equally capable of coming forth in human affairs. Acts of courage, large or small, prepare for another generation to live more freely. Story elements I hope will spark the reader’s imagination of what is possible and what still needs to be done.

The intention is to apply reason and courage to civil discourse.

Enslavement

The 1619 Project of the New York Times promotes awareness of 400 years of slavery in America and brings forth vital dimensions of its legacy. These dimensions have been lacking in our collective imaginations and knowledge of history. I value this instruction and hope to rise to the tasks I have given myself, to write a novel set in the period of slavery yet which cannot depict the full force, or the complicated legacy of its wrongs. Read more in my blog post about the 1619 Project.

Many compromises continue to shape our identities and ideals in the United States. Starting with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, uneasy balances were holding the young nation together, yet those compromises were also deeply abusive to human lives. Lawmakers proposed solutions for gradual change, but they were not ratified. Black Codes in Missouri were enacted to deny civil rights. But acts of civil courage must have attepted to overcome them, until civil war and ongoing civil rights movements came to restore them. I’ve tried to represent those acts of courage in The Compromise.

Courage and Civil Discourse

My character Otis was a captive when he expected to be free. He risked his safety and his future for the freedom of others, and his friends took those same risks to free him. Abolitionists had to work secretly or risk reprisal. In Missouri, there were laws to punish those who helped slaves escape or who openly opposed slavery. The Compromise attempts to expose arguments and beliefs on multiple sides of the issues. Those issues are revealed in the dramatic action and dialogue. The intention is to apply reason and courage to civil discourse.

Otis looked at all of us. “My friends, you came to protect me and I'm alive in this moment because you did. But we can’t run from what our forefathers put here. Time alone will not give us the nation we want. Words alone will not do it. The law made commerce in human lives a political game of degradation that will endure. Changing the law and its origin in belief will take more than one life, and this life is all I have to give.” He turned to the walnut tree where he almost got hung then rattled the chains between his hands. He said, “The same hell sank my people in endless sorrow, the hell we are meant to rise from together. Let it be now.”

The marshal shifted on his feet and said, “You have faith in the law, Mr. Roche. If you defend yourself before the judge, I believe the people will fill the courtroom to hear you. But take heed, Judge Carmichael will be firm to show the strength of law in Missouri.”

Most of use knew this was likely true. The stronger the singular human voice, the mightier the sword against it. This is what Otis refused to believe.

The Compromise, “Meriwether, 1845”

Time alone will not give us the nation we want. Words alone will not do it. The law made commerce in human lives a political game of degradation that would endure.

Their acts of courage and acts of compromise

I hope that setting my story in Missouri will bring to light some of the lesser-known phychological and existential experience of human enslavement. With no wish to sensationalize the past or burden the young reader with factoids, I want this historical fiction to reveal the failures and the strengths of moral reasoning across time. My investment in the past is for the future.

Diane Mutti Burke discusses slavery in Missouri in her study On Slavery’s Border. Her book is based on extensive research on small slave-holding households, 1815-1865. Her summary of background history matches the premise of The Compromise. In Missouri, more poor households were composed of one enslaving family family and one enslaved family. Typically, yeomen farmers had not been raised in enslaving families. They constructed the relationships as they subsisted on the land and were socialized within their communities. Enslaved men and women worked in the fields beside the free-born and raised their children amid complex necessities and principles. Surely, economic decisions strained against familial bonds, religious responsibilites, and the law. This describes the novel’s family in Stoneville.

Upon arrival in Columbia, the young women must adapt to a socially stratified society. They struggle to form new identitiies, when family bonds and new ideologies are in conflict.

In the scene that follows, a wealthy white woman wants to prove that poor illiterate women are worthy of education. She asks Mariah difficult questions about religion and politics. To help her, Scarlett, a brave young abolitionist calls out.

“Do you believe that slavery is morally acceptable?” she asked.

“No, Ma’am.” All of a sudden, I felt as ornery as the old women of Stoneville, too stubborn to hold my tongue. I said, “No. It breaks the commandment. Slavery’s stealing what ain’t yours, and giving no credit for the work that’s done.” I regretted it right away. Of course it was wrong for someone in a maid's striped dress to have an opinion like that.

Some ladies turned their eyes away. A girl gasped “Hillbilly” and someone else said, “Forgot her place!” The room felt like two magnets repelling.

Then a young woman’s voice rose above the others. She cried out, “Prosperity that depends on human enslavement will not prosper the union.”

The Compromise, “The Liberator 1840”

I want this historical fiction to reveal the failures and the strengths of moral reasoning across time.

Women’s Rights

Women could not inherit or control property. Women’s property rights were only beginning to change in some states. Literacy, access to education, and the efforts of women’s rights advocates made gradual changes, culturally and politically. Harriett Beecher Stowe, famous abolutionist and author, said that married women passed out of legal existance.

"[T]he position of a married woman ... is, in many respects, precisely similar to that of the negro slave. She can make no contract and hold no property; whatever she inherits or earns becomes at that moment the property of her husband.... Though he acquired a fortune through her, or though she earn a fortune through her talents, he is the sole master of it, and she cannot draw a penny....[I]n the English common law a married woman is nothing at all. She passes out of legal existence." -- Harriet Beecher Stowe

Wikipedia: Married Women’s Property Acts in the United States

“Mark my words, prepare yourselves to earn a living.”

Women’s Property Rights

Women’s property rights and education play fundamental roles in The Compromise. Mariah is unable to inherit her family’s property. This inability changes the course of her marriage and her siblings’ futures. Even the academy directors do not own the academy. Their inability to sign contracts sets the trajectories of many lives. Women in my story lead their families and earn their livings through labor, but they do not control their destinies.

Mrs. Starr spoke in a strong shrill voice. "Prepare yourselves to earn a living. Do the two of you have a plan?"

I mumbled, “No, Ma’am. Not really.”

“What was that, dear? I don't worry about you, Mariah. You know how to roll up your sleeves and hitch up your skirt. You’re as strong as a mule.”

Tingles rushed to my face, and she cleared her throat. “That be as it may. In Missouri and in all these states, women cannot sign contracts like men, but we do the work and everything good in this world comes because of that. With good fortune, you will settle where you gain property rights.... But mark my words, prepare yourselves to earn a living.” Mrs. Starr stood to leave the parlor. She added, “That’s alongside the work of running a household of hungry children and cleaning up the man who made them.”

The Compromise, “The Proposals, 1842”

Strengthening the rights of women continually improves society, and this dream sent many of our ancestors west. The next generation, my great-grandmother became a property owner in Sonoma, California by the second half of the 19th century.

“Once educated, we can keep our minds free while our bodies bend and break with trials.”

Women’s Education

None of the novel’s female characters could go to college, and my female protagonist was not allowed to access formal education. She was illiterate. Informal relationships provided access to knowledge. Even when that access to knowledge and participation was limited, women began their march to equal rights. My great-grandmother returned to paid domestic work in order to let her daughter, my grandmother attend UC Berkeley at the turn of the century. They set up housekeeping in a tiny place at the corner of Milvia and Virginia. My maternal ancestors did not have a strong hold on the social class associated with higher education. They became teachers like me.

“One day Jefferson’s words will not be lies.”

Soon after their arrival in Columbia, Otis takes his sisters to see the new University of Missouri.

“No," said Otis, "you and I are not welcome at the university now except to dirty our hands.” He pointed behind us and said, “Today the shapes of buildings are drawn with string and their designs are on those rolls of paper. One day Jefferson’s words will not be lies. You watch. ‘Truth advances and error recedes, step by step only.’”

Mariah has many adventures, but the greatest is learning to read in a great library. Her teacher was a young woman her age, Margaret Jane Mott.

I wrote down some of what Margaret said on slips of paper that I kept in my apron pocket. One said, “Once educated, we can keep our minds free while our bodies bend and break with trials.” I needed those words because I was cleaning and putting on meals for people who never really saw me as more than a cleaning rag or a serving spoon.

Of course, my experience as a teacher is played out everywhere in this novel. Even while formal education through high school is increasing worldwise, I’ve had many students over the years that were functionally illiterate, children and adults. My years teaching English to immigrants, many of whom take low-paid service jobs, put me in Margaret’s world. She is preparing to become a teacher, one of millions of women, who volunteer or subsist as teachers. The students come, not for degrees, but to learn and keep their minds free while their “bodies bend and break with trials.”

Adult educators give “little slips of paper” to those who do the work of farming, cooking, and cleaning. We’d better use that paper well. Then we can have a society where thoughts can be free and participation grows. This novel is my little slip of paper to be kept in a pocket.

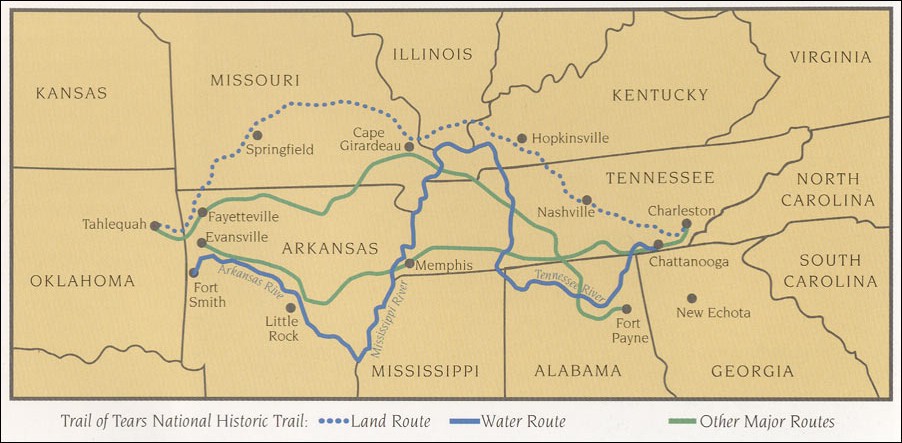

Indian Removal

“In town they said it was federal law that took Mother. Federal law might bring her back.“

Cherokee Removal took place between 1836 and 1839. Cherokee, along with many other Indian peoples, were forced from their ancestral lands in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Missouri, and Texas. They were resettled in Indian Territories, including present-day Oklahoma. The Cherokee were a matrilineal society as opposed to patrilineal, the European and American society dominant in the US. In matrilineal societies, indiginous women had more political and economic rights than immigrant women. Much of the story hinges on this fact. Raised by a strong mother with a compassionate and liberal mind, my characters enter a world in which they can be critical even as they appear subservient. Having a good moral compass is better than many other possessions, but Mariah learns early that those who control the land control our primary relationships and our means of production.

It was Mother who raised us, left her mark on our upbringing, and kept us together. But what followed in the letter was a lightning strike, strong enough to split a tree.

Then the fur trade failed and laws were passed in Washington. Cherokee people, along with other Indian tribes, were put in prison and forced to walk to the territories. Those federal agents, they came through Stoneville and took Mother that winter of 1838.

The Compromise “The Letter”

A central question of the Compromise is whether Mariah’s indigenous women’s knowledge will serve her as she faces social stratification and urbanization. Margaret asks Mariah to measure the truth of what she learns against the knowledge she already has. One important decision about culture takes place in a short conversation between teacher and learner on the topic of nature.

Margaret read to me a book called “Nature” written by Mr. Emerson. She said I already understood nature though I might not believe I did. She read, "Nature is not fixed but fluid; to a pure spirit, nature is everything.”

“Mother said things like that.”

“She did?” Margaret seemed surprised.

“Well no, not in those words that I recall. But that’s what she would have said. She knew that water and soil gave to us without our asking for anything, and that’s where we could touch heaven, by reaching down, if we had a mind to do so.”

“I thought your mother was a Presbyterian.”

It was my turn to smile like I was hiding something.

Mariah will have to make a compromise on how her mother returns. I hope this difficulty can inform the second book.