Bildungsroman, the coming-of-age story, is a powerful cultural idea. The story accounts for a character’s moral education through the formative years. Typically, a sensitive person goes into the world to answer life’s questions. It begins with an emotional loss that sets the course. There are helpers and challengers along the way. The goal is maturity, achieved gradually and with difficulty. But the protagonist typically masters social norms and finds safety, belonging, and love. Comedies end in marriage, and so do most coming-of-age stories, most notably, Cinderella. How does The Compromise deliver on the cultural expectation of this genre?

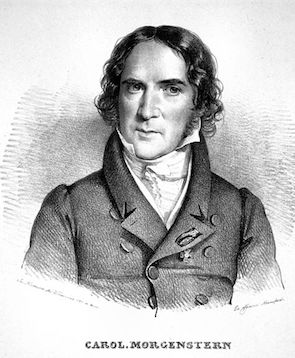

Before answering, I must bow to the cultural ideas indicated by the paragraph I have just written. Bildungsroman is a literary genre based on a term coined by Johann Karl Morgenstern around 1800. It could be translated: a novel of moral education.

The popular genre, bildungsroman was a term coined by German theorist Karl Morgenstern around the year 1800. The 19th and 20th centuries gave us many novels in which growing up meant leaving an assumed order to find or make a new one that might integrate personal truths and public realities. I am working solidly in this tradition as my novel wends it way to and comments on romantic comedy.

K.M. Weiland has written extensively on archetypal character arcs in order to help emerging writers. As did Morgenstern more than 100 years ago, Weiland sees coming of age as an integration. For her, it leads one to overcome fear and become empowered in the world. Weiland begins her blog post on The Maiden Arc, as follows:

“The First Act of the human experience—roughly the first thirty years—may be thought of as a period of Initiation. It is a period of integrating the parts of one’s self. In many ways, it is a period in which the overarching, symbolic antagonist may be thought of as Fear. We use the arcs of this period to overcome Fear and discover our own empowerment as individuals within the world.”

In the process of psychological integration, we need interaction to support our growth and cultural tools to overcome fear. In The Compromise, those interactions and tools provide their own complications. Critical awareness of culture can be cultivated. While guiding characters and hopefully readers through conflict, novels also regulate cultural identity and train a Western perspective as they adhere to point of view. Centuries of novels work together to form genre expectations. These expectations can be questioned.

The craft of writing is a set of cultural expectations. This is discussed in Matthew Salesses’ 25 Essential Notes on Craft: Rethinking Popular Assumptions of Fiction Writing. His new book is Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping. The point of view of my narrator may be akin to the “split-conscious” identified as a postcolonial experience by author, Michelle Cliff. I must also recognize my one-time professor of rhetoric and women’s studies, Trinh Minh-Ha for the many ways she sparked postcolonial awareness.

The great Toni Morrison shows how cultural expectations can work and be reworked in fiction. Her narrative voice gains power through the long form of her novel, The Bluest Eye.

Adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs– all the world had agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every child treasured… Traced the upturned nose, poked the glassy blue eyeballs, twisted the yellow hair. I could not love it. But I could examine it to see what it was that all the world said was lovable. Break off its tiny fingers, bend the flat feet, loosen the hair, twist the head around…. How strong was their outrage.

The Bluest Eye (1970), Toni Morrison, winner of the Noobel Prize in Literature

Quietly, I hope, I reference The Bluest Eye in my scene, “In the Mirror.” Through a maze of cultural influences, I work towards “a theory of how it feels to be alive.” That theory tries to embrace paradoxes and hold complexity longingly. Maybe one can create a life of compassion even when storied union and reward are not assured.

“A theory of how it feels to be alive”

Jane Smiley, 13 Ways of looking at the Novel

Cinderella

In the process of constructing gender, social class and racial identification take shape in the family.

Cinderella is a folktale of increidible diffusion around the world. It recounts, what Wikipedia says is “a story about oppression and triumphant reward.” In the Disney version, the maligned step-sister, who must clean for others, ascends to the throne with magical help. She embodies womanly virtue and suffers abuse as patiently as a saint. The Fairy Godmother makes a beautiful gown as a reward for the young woman’s pure heart.

The laws tried to strengthen marriage by limiting opportunities for women.

The mythic elements of Cinderella are easy to find in The Compromise. Both stories involve a young woman preparing to enter society as a wife. the young women do so without the advantages of financial security, a loving mother, or equal opportunities. In the 19th century, American society offered women few choices for employment, marriage, and childbearing. The laws tried to strengthen marriage by limiting opportunities for women. Divorced women lost custody of their children, and women could not own or control property other than–in some states and with strange and tragic consequences–human chattel.

Life may be true and honorable when it is neither fair nor triumphant.

Mariah’s bildungstrom is much indebted to Cinderella and can and should be interpreted with the trope. However, the role of illusion is very different as revealed in the fitting of the dress. Cinderella is granted a dress and a coach suitable for the ball. Mariah’s “coming out” into society is more humble. The Compromise gradually reveals how the protagonist sacrifices illusion and maintains her honor. These elements of character propel the story and propose a theory of awareness. Life may be true and honorable when it is neither fair nor triumphant.

The immorality of inequities is a very common theme in 20th century novels. So much rides on partnerships and legal agreements, romance becomes an essential part of a coming-of-age novel. In The Compromise, Mariah begins the “mirror” scene in trepidation.

One Sunday afternoon when I was nearly eighteen years old, Mrs. Starr asked me to see Eliza upstairs for help with my dress and my hair. I was going to have a special guest that afternoon, a man. I washed and crept upstairs feeling scared. We knew this day would come. I had to meet my future husband.

Illusion and Affection

“My sister looked at me in the mirror, and for the first time ever, I saw our faces side by side.”

The Compromise, “In the Mirror 1841”

Like Cinderella, Mariah must dress and present herself to be accepted into this role. She must transform from a cleaning girl of low rank into a picture of refinement to pique the imagination of the prince, a single man. This requires the help of other women. She is initiated (or indoctrinated) into the charms of women– notably hairstyles, corsets, lace, and makeup. Eliza, Mariah’s half-sister, stands in for the Fairy Godmother. For two years, Eliza has been “trained” to serve the “white ladies upstairs,” whose stated ambition is marriage. Eliza has set the scene for her Cinderella to make a good impression.

“You just wait,” she said, “You’re going to feel like a sweet apple ready to get sliced up for a pie.”

I hope my readers see that I signal an ironic treatment. However, my own half-sister had the same role in my childhood. She contributed her charm-school ideals of beauty to my upbringing. She had outstanding bearing, intricate makeup, and spunky bright red hair. She used her curling iron to place ringlets in my two thick bunny-ear pony tails. I can still remember her soft midwestern voice. I believe I hung on every word and followed her into the improbable realm of fake eyelashes.

Familial affection mediates values. In the process of constructing gender, social class and racial identification take shape in the family.

The dress and corset do not allow a woman to do menial work.

She said, “Through no fault of your own, your waist is long and thin, about the same as the rest of you. The corset pulls you in here. And it's going to make something of you up here. All this cloth is going to push you out down there. It'll make what is called an illusion.”

I nodded. “Improvement?”

“Yep, as long as you can breathe and not let anything bounce up and down and remember never, never bend over.”

The dress and corset do not allow a woman to do menial work. Unlike Cinderella and many young women, Mariah recognizes the limits of charm. It’s a single day of illusions. Will the feminine image activate a man’s affections and will his affections save her from future drudgery?

With her help, I put the dress on and took it off, so she could adjust the fit. “When you wear a dress like this,” she said proudly, “others will do your stooping and bending!”

“How long is that going to last?” I felt contrary. Stooping was in my line of work. One afternoon in a corset would not change that.

Eliza smirked. “It makes this day more special. You know that. Now you sit here, like the lady you are, and let me look at you.”

Reckoning in the Mirror

Pragmatist Eliza has internalized the norms of beautify for white women, and it gives her the upper hand in negotiation with her humble half-sister. The moment of reckoning comes when the sisters look in the mirror together. We see why Mariah came to the dress fitting with trepidation.

My sister looked at me in the mirror, and for the first time ever, I saw our faces side by side. She made me happy, so I had some of her color in my cheeks but the mirror also made it hard to keep the pleasure of being together.

As she worked on my hair, her eyes darted up to see us together, but her eyes lingered on herself. She was more beautiful. Her eyes were baby-blue, wide open like a doll. Mine were black and squinty compared to hers. She had rosy freckles, and I had dark moles. She had reddish-brown curls at the nape of her neck. For me, it was tar-black and straight.

Her face was heart-shaped like drawings in fashion magazines. I had a flat face with parts that didn’t match. I had such angles at my elbows and shoulders, no corset could make curves. Her breasts were plump and dove white, but mine weren’t. No, I was the color that could disappear on a hillside let alone in a mustard colored dress! Tears formed in my eyes.

In many turns of dialogue and reflection, my protagonist is tested. Will the protagonist sacrifice her inner truth for the powerful image?

Racialized Standards

Marketing skin lightening cream and hair straightening procedures, commodification seeps quickly into the American Dream.

Comparing herself to her more beautiful half-sister is painful because oppression exists. From eye color to hair texture, women are subject to heavily racialize standards of beauty. Beauty product industries attest to their power. Marketing skin lightening cream and hair straightening procedures, commodification seeps quickly into the American Dream.

“You might be a late bloomer,” she said without a smile. “I do see some lights in your hair and cream on your bosom where the sun does not darken you. You almost look like a white lady, and with proper care of your skin and hair, you will.”

Does Mariah give up her inner truth along with her social control?

For Eliza, proper care is what makes a woman look white. The idea of racism can hardly enter their consciousness. However, it should enter the reader’s. Subject as she is to powerful standards and high stakes, Mariah is unreliable. The signs of racial difference in their appearance tell the stories of their mothers. Eliza’s biological mother was a white woman, and Mariah’s was Native American. Inola raised them together from early childhood. There is an interesting moment when Eliza lets herself express her own envy. Mariah looks more like the Cherokee mother they both loved and lost.

“You look like her,” Eliza said, “like Mother with high cheekbones, her warm skin, and dark eyes. You belong to her more than I ever will.” There was sadness in her voice.

“But you’re beautiful, Lizzy. Look at yourself.”

I believe Mariah is kind when she answers her sister’s legitimate feelings of loss with a compliment. Interactions and relationships are so deeply layered. Intimacy and affection carry risk, but Mariah rallies in a move that will return several times. The missing parent is found within.

There was a flash when I saw her, our mother in my face, and she was smiling at me, at us, her girls now women. She looked into the distance over our heads. A sandstorm was coming or a drought.

Betrayal and Loyalty

She struggles as oppression threatens to be internalized.

Like Cinderella’s step-sisters, Eliza swings into action to betray Mariah several times. The betrayals are delivered in sweetness. She complains about Mariah’s eyes, saying that she squints and says that is unladylike, a failing that needs correction. She provides a dress that is unflattering in color. She does not comfort when it is needed. She enforces standards that undermine her sister’s sense of her own physical body, her readiness as a woman, and her family history. Eliza might be acting out her own pain and envy, and such lack of awareness constitutes a betrayal. If we anticipate the causes and effects of these small betrayals, either sisterly affection will be broken or Mariah’s esteem with be lowered.

I thought about it. I couldn’t stay out of the sun or keep my hands clean while I worked in the garden. I did get tired of the dirty work. But the land was my home, or was it? This color on me was not right. I looked like dirt and more dirt. I wiped my tears and felt out of balance like I might stand and fall over. How could I refuse my sister who wanted me to be like her? Maybe there was a good reason to be better, look better than I did, or maybe not.

She wavers. She questions. She struggles as oppression threatens to be internalized. Does Mariah give up her inner truth along with her social control? No, she must ride the tension of the scene and this bildungsroman to the end.

In the next scene, Mariah meets George. The reader will see what Mariah does not: George is an utter disappointment, lacking in romantic inclination towards her. It’s a business contract and this meeting is a formality of the dominant patriarchy. Her female companions, all of whom implicitly support the patriarchy, make their heartless comments.

“You did it, Miss Mariah,” said Hester. “You’re an engaged woman!”

Eliza said, “You took his rose, so it's done. It’s already old, and so is he. It doesn’t matter. All you do is smash it in a book anyway.”

My heart started beating again like a live person. I had two or three years to work things out and live my life with my own self. I felt light as a feather. “I’d like to walk around the block in this pretty dress, Eliza.”

“That’s right. Feel proud. You’re an American woman starting today.” said Mrs. Starr. “Eliza, you go with your sister and do nothing but stroll around for a few minutes. Carry these two parasols to protect your skin. Hold up that skirt so it doesn't drag!” And that’s exactly what I did.

I heard what she said, that starting that very day, I was an American woman. I felt the breeze on my cheeks like I had embarked for a new land and it was my right to walk with my head held high. I wanted that feeling to last, so I did not ask what I was losing or how long it would last.

Traditionally, a woman is both inside and outside of culture, shaped by its dominance and heroically holding her own. This is the narrative tension and the precious humanity I want my reader to feel throughout the novel– the best fruit of the genre– the hopeful young heart and the clear cynical eye compete for a place of truth. This reveals our theory of what it feels like to be alive.