This post is an expansion of “Echoes” posted a year ago. It builds on the notions of echoes, memories, and intertextuality by adding learning design, music theory, and more scenes from The Compromise.

If we write and teach well, echoes return. The useful phrase is used again. The fertile image is reimagined. The play of light on rings and the echo of sound on stone are rarely spoken of, so they find their places in art. Few things in writing The Compromise give me as much pleasure as hearing voices return in the text, and in writing this blog post, I reflect on how it works in literature and in my own writing specifically.

“Poetry is above all a concentration of the power of language, which is the power of our ultimate relationship to everything in the universe.”

Adrienne Rich (1995). “On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966-1978”

Learning Design

In learning theory these echoes have been called interleaving. Learning is most effective when new content comes and goes and returns. It needs to be layered. Cognitive psychologists discuss interleaving in the book Making it Stick: The Science of Sucessful Learning. Readers, in noticing themes and images, are engaged in learning. Equivalents are replaced by echoes and neural networks are strengthened. The similar concept, intertextuality will be discussed later in this post.

It is also like music that returns to the tonic, the key that was mysteriously planted in our minds from the opening notes. We know the song or symphony has ended when the tonic returns like a boomerang or a comet. The music took us far from home, challenged us to lose or anticipate its path, but in the end we find ourselves renewed and delighted.

Because echoes are discovered more frequently than designed, it reminds me of nature’s convergent evolution. In human communication, the circle makes a spiral when the message carries to another who gives it new meaning across time and space. Augmented by a written text, the art of language is one of the mysteries of human experience. It is so common in our lives that we forget what it is.

We reconstruct our internal polarities each time a little differently.

Words accrue meaning through use: in culture, in conversation, in dreams, and in literature. Writers find these seed-images by entering the “half-known world” and trusting. Some of the images we plant will germinate. My writer friend, Terry Tierney does this admirably in a recent story. African violents, dry, radioactive, or flowering, return just often enough for the reader to see the design. They come to represent the care and feeding, or the fear or neglect, of the beloved. The hesitant young lover takes the exit. We turn the page to see how or if he returns to the girl in the hat.

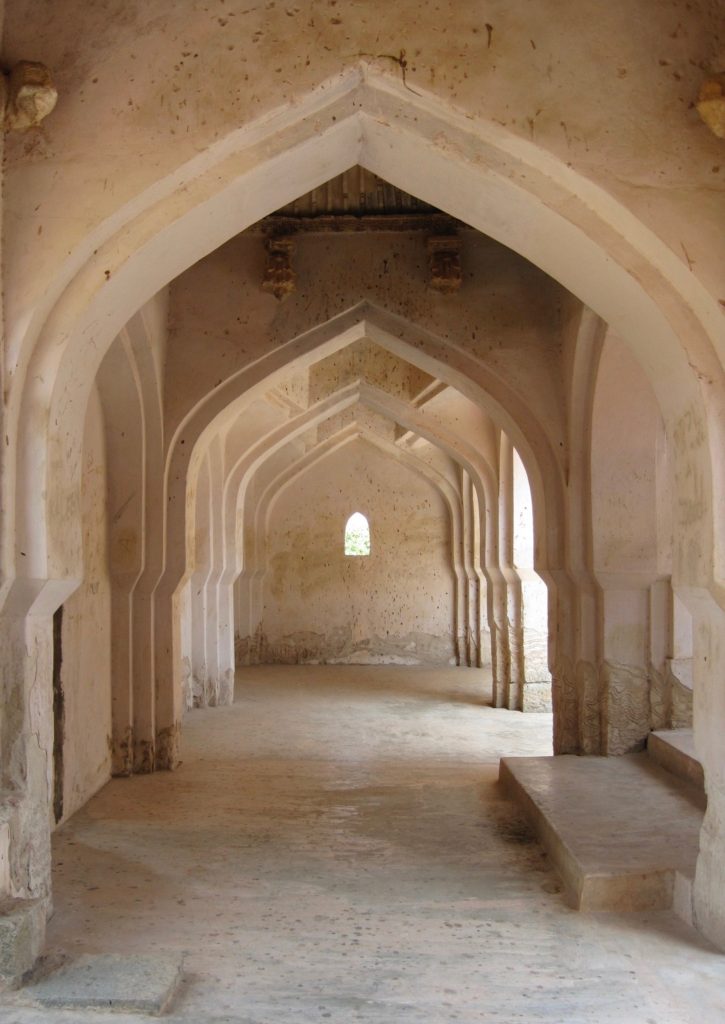

Thresholds

Hovering between upward and downward arcs.

Looking back at the beginning of The Compromise, I see how it works. I stake out several images in the first events that can and will return and grow: silver buttons on the jacket, the dream of the swallow, cherry pits, and unripe groundcherry and dewberry. I want to show my readers how it works early on. One of the first is the dream of the swallow.

I woke to sounds of wild things stirring before the sun was up. My last dream was of a barn swallow hovering, balancing between upward and downward arcs. Then she rose, letting the current take her. Uneasy times a'coming. I inched into my coat to let my brother and sister sleep, tiptoed outside with Nanny Goat to let her forage and slipped back in to get my boots and the knife.

The next morning they pack to leave the only home the sisters have known, where their livelihoods had the uneasy balance of wild and domestic. The image returns in Time’s great pivot of coming and going, the threshold worshiped by the ancients in many cultures.

"Now get ready and say goodbye to what you’re leaving behind.”

Standing on the porch, I closed the door firmly, and touched it the way we always did to call on the sacred wood before a journey. I saw it then, how I had to hold still in midair like the swallow feeling both joy and sorrow.

Eliza and I kissed Nanny Goat goodbye and set her free.

Otis said, “Go find your Billy.” We laughed because she would.

The Compromise, “Stoneville 1839”

Childhood establishes the tonic, perhaps in the key of C major. When it returns in adulthood, it will be changed. Mariah returns to that threshold and each time it is different and the same. There is music in the small ways of my historical characters, familiar and also estranged from our time. I want the symphony of my novel to satisfy its promisses even with uneasy times a’ coming.

Sure enough, the image of the swallow returns deep into the novel. Mariah says good-bye to Otis. He is going to be tried for crimes he knowingly committed. It is unlikely they will ever meet again.

Otis looked up and saw my tears. They were the same old tears, for Mother, for Eliza, and now for him. I knew how bad this was but held myself from running to his arms like a little girl. I pushed the next sob down and tried to smile. He pointed over my head and drew a line in the air west. “Stay your course!” This meant he wanted me to leave his side, to live my own life. He smiled his broken smile, and I closed my eyes to hold it firm. For a moment, we were in midair like two swallows between the upward and downward arcs. We lifted on the updraft for a final moment together.

The Compromise, “Meriwether 1845”

Enactment to Action

Stepping from enactments into action is essential to coming of age. One of the most stunning discoveries mapped out in The Compromise is how a memory from childhood influences the future. For me, early reading in archetypal literary criticism (Northrop Frye), structuralism, and later reading in semiotics and post-structuralism are major influences. In the novel’s fictional 1820s, Otis learned to read the Columbian Orator on the sly. He was allowed to watch the white children prepare their orations. A girl nicknamed Chubby performed The Plea of Thomas Muir by the Scottish radical reformer (1765-1799).

Chubby changed her oration to the Plea of Thomas Muir. It’s what he said during his trial for treason. She started on her knees and folded her hands under her chin.

I may be condemned to languish in the recesses of a dungeon. I may be doomed to ascend the scaffold. Nothing can deprive me of the recollection of the past; nothing can destroy my inward peace of mind, arising from the remembrance of having discharged my duty.

We boys riled against what we saw as the arrogance of a girl, but her rendition of Thomas Muir was good. I made all the boys quiet down to let her do it again.

The Compromise “The Governess” 1825

The Plea

When Otis is arrested in 1845, he is bound and forced to go down the steps on his knees. By reciting the famous Scottish Plea on the steps of the University, Otis claims his right of free speech. Ironically, his arrest fulfills the accusation that he was inciting a riot.

It does not stop there. Years earlier Otis had taught the Plea to the girls he helped raise, Mariah and Eliza. Upon learning that Otis recited it while forced to kneel, his half-sister Mariah realizes that the arrest was a plan to speak against slavery. Using his kneeling body and the exhaulted setting, it is no longer child’s play. The oration is a speech act. The basic constitutional protections of free speech and assembly had been suppressed by Misouri law. As in Muir’s case, the apparent effect of piety and bravery was sedition. Otis is also on a path of martyrdom.

Mariah gets news of the arrest from the school director, Mrs. Starr, but only Mariah can decode it.

“I knew it. This's his duty. He wants a public trial because he will have a chance to speak, to make his case before the judge and jury.”

“Mariah, are you saying Otis set this up and wants to die?”

I nodded. “And to incite rebellion if he can. He knows the law. He knows that running north makes it worse for those who stay. And he saw what was happening to freemen around him, exiled or imprisoned, but he stayed. Why else?”

“Heaven help us!”

The Compromise, “Inciting Rebellion 1845”

To affirm his faith in the system of laws and apply the skills of an orator, Otis is looking for a public trial. His corrupt jailors and the vigilantes are looking for a spectacle of a different sort. Strange bedfellows. Otis is leaving for his trial in Jefferson City. The lawmen come to transport him and the abolitionists are there to watch and protect. Mariah sees her brother come out of the courthouse in shackles.

Otis turned to the people. “We cannot be shut out for all ages from the aspirations of the human soul. Today we go to the capital to discharge our duty, and that is to be heard!”

There were some shouts of approval. His orator’s voice picked up strength. “Someday, we will fill the universities and the great capitals of this nation, not the fields or the prisons.” His voice radiated from the walls of the courthouse. These shackles cut the flesh but not the human spirit.”

More people shouted their approval. Then others heckled and shouted against them.

“You don’t belong here!” bellowed a man.

“Go back to Africa. This is our land!” shouted a woman.

“Let him hang! let him hang!” some cried.

Hester pushed me away. “I’m called to go and nothing’s going to stop me.” She pushed her way forward.

Otis faced the hecklers and his voice seemed to fill the sky. “Our nation is a brotherhood, a family, and you are my brothers and sisters, different from me and the same.”

He seemed to look at me, but I couldn’t be sure....

He turned to the abolitionists. “Whatever happens henceforth, hold on to our cause, your dignity and your peace. There is no progress without struggle. Change the laws and keep the union before you count your dead in every corner of this land. Look forward! You can’t plough straight if you keep looking back. Hold on.”

The Compromise “Moral Freedom 1845”

Who will succeed? Will that little brown notebook that passes from hand to hand let Otis live? He might do what his sister would do, live on without the grand myth, and let the story continue with its contemporary echoes. The outcome of his trial will wait years to be revealed to his sister whose life must take a different turn.

But a new scene has a noose, a man in shackles standing on a wagon, and a young woman in a tree with a knife!

Intertextuality

The tools are language and image made evocative by their intertextuality.

Is this going to work? I’m making it up, of course, but I’m trying to use proven tools designed by others. If I do it well, language and image will evoke through their intertextuality. The term intertextuality was coined by Julia Kristeva and was influenced by Bakhtin’s Dialogic Imagination.

“Truth is not born nor is it to be found inside the head of an individual person, it is born between people collectively searching for truth, in the process of their dialogic interaction.”

~ Mikhail Bakhtin

Balance

This aspect of the plot reminds me that I must continually work to keep my narratives in balance. Otherwise, Otis will become a singular male protagonist on a heroic quest. Mariah could be relegated to feminine observation, domentic drugery, and pain. Similarly, Otis might languish as a victim, internalize racism as self-hatred, or identify with his bullying and paternalistic captors. Mariah could drown in feeling while trying to save everyone else. Indeed, Otis and Mariah pass through these positions. I have cut many passages that seemed to prattle on in self-doubt.

I have two lead characters, but psychologically, they could be aspects of one consciousness. One can be strong and the other flexible. One can seek depth and the other height. I can let them dance in the mind, upstage one another, and go off stage in different directions. I hope they enliven their archetypes with equal heroism in the reader’s mind.

“Male domination is so rooted in our collective unconscious that we no longer even see it.”

“Every established order tends to produce the naturalization of its own arbitrariness.”

Pierre Bourdieu

“It felt like I was talking nonsense to the moonrise.”

Come Back

There are many more echoes in the novel. One is literally and figuratively an echo across the echo chamber of the stone quarry. On her way to Stoneville, Mariah discovers Sweetie, a pregnant teenager eating berries atop a wild horse she tamed. The girl is heading north to escape cruel slavery. Mariah tries to help with food and shelter, but the girl runs away again.

I called for Sweetie, but it felt like I was talking nonsense to the moonrise. The hill gave me a view of the red-stone quarry below and the road to town. I called “Come back!” and heard the echoes from the quarry. Come back. Come back. Sweetie had been enslaved all her fourteen years, so she might be hiding from me, afraid that I’d tie her up and sell her or divide her from her newborn child. She had no reason to think otherwise. As bad as my life was, I did not have those fears of another human being.

The Compromise, “Come Back 1844”

I don’t want to give away the story of Sweetie, but sometimes no amount of work is enough. We are human and we are mortal. We cannot hold on, whatever our intention. In a strange way, calling Sweetie brings both Sweetie and Otis back to Mariah. The cliff becomes a place of hearing the answer in the question.

Reading and writing, we find the spiral and the echo. On the cliff above the quarry, Eliza waits for their mother to come back. Years later, Mariah calls for Sweetie to return, and during the blizzard, there Mariah is turned away from death by those she loves and fears. Then these structures are like learning. We reconstruct our internal polarities each time a little differently. We might cry out at the cliff of our unknowing, hear the ragged report, and pull back to keep on living.